A month ago, I flew to London to visit “The EY Exhibition: Impressionists in London: French Artists in Exile 1870-1904″ at Tate Britain. Its premise is summarized by the Tate: “In the 1870s, France was devastated by the Franco-Prussian war and insurrection in Paris, driving artists to seek refuge across the Channel. Their experiences in London and the friendships that developed not only influenced their own work but also contributed to the British art scene.”

![IMG_6912]() The exhibition is huge, and the galleries were crowded on each of the two days I visited. There is a great deal of beauty on display, but it’s also a very ambitious, cerebral show, so you have to pace yourself.

The exhibition is huge, and the galleries were crowded on each of the two days I visited. There is a great deal of beauty on display, but it’s also a very ambitious, cerebral show, so you have to pace yourself.

James Tissot fought to defend Paris in the Franco-Prussian War, served as a stretcher-bearer, participated in the bloody Commune the following spring, and fled to London in June, 1871. For me, this show was an opportunity to view several works by Tissot never before displayed in public, as well as many of Tissot’s most intriguing oil paintings in a single venue. These have been cleaned for the occasion, and the colors are as vibrant as if they’d been newly painted. I was one of many visitors transfixed by the restored beauty of Tissot’s brushwork and the details revealed.

I’ve created the following virtual tour for those who cannot make it to London to see this – or who have not yet seen it, and may soon. Commentary is mine unless otherwise noted.

In the first gallery of the exhibition, with its walls painted a somber aubergine, I was one of many fascinated by sketches and watercolors Tissot made during the Franco-Prussian War. Since I have a special interest in his life and work during the war, the Siege of Paris, and the Commune, I’m afraid I may have impeded traffic in this section of the gallery.

For additional information on this tumultuous period, see my posts:

James Tissot and The Artists’ Brigade, 1870-71

Paris, June 1871

London, June 1871

The Artists’ Rifles, London

Tissot’s elegant watercolor, The Wounded Soldier (c. 1870), acquired by the Tate in 2016, is a singularly beautiful image of a restless young man in uniform perched on the arm of a sofa. Thanks to the staff in the Tate Study Room, I had a chance to view this work closely on an earlier visit to London in the weeks before this exhibition. It likely was painted within the city walls of Paris, where the wounded were brought to convalesce in public buildings. The Wounded Soldier is James Tissot’s most sensitive, profound, and arresting work and shows him in a new light. The exhibition text notes that he kept it in his studio all his life, never exhibiting it. This is the first time it has been displayed in public. Photography is prohibited in the exhibition, but click here to see an image of it.

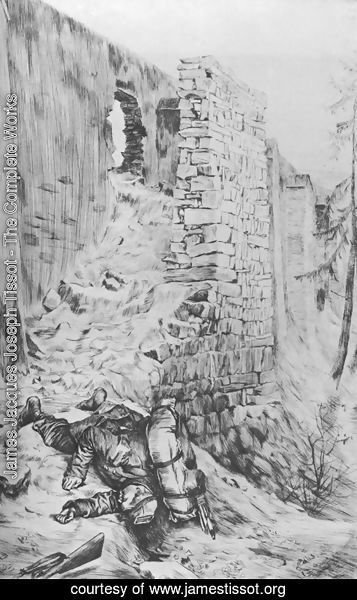

In the bitter aftermath of the war, French citizens engaged in a bloody uprising against the new republican government. My research indicates that Tissot participated in the Commune in some way, and like many of his peers, including Manet, Degas and Renoir, he seemed sympathetic to the plight of the Communards when the government ended the standoff with mass executions. Tissot, renowned for painting the ruffles and ribbons of women’s fashions, documented this period in French history in a way no one else did. The exhibition features his eyewitness account in watercolor, The Execution of Communards by French Government Forces at Fortifications in the Bois de Boulogne, 29 May 1871 (private collection), displayed in public for the first time. This horrifying image was sent along with a letter to Lady Waldegrave (1821 – 1879), a prominent Liberal hostess in London whom Tissot likely met through J.E. Millais, if not his friend Tommy Bowles (Thomas Gibson Bowles (1841 – 1922).

The letter has been expertly translated from the original French by the exhibition curator, Dr. Caroline Corbeau-Parsons, Assistant Curator 1850-1915 at Tate Britain. In it, Tissot writes a graphic stream-of-consciousness narrative of executions of Communards, or suspected Communards, by government soldiers. Dr. Corbeau-Parsons, who organized the exhibition, notes that his “broken language” and his lack of grammatically correct accents betrays how traumatized he was in witnessing this horror, and yet Tissot is surprisingly thorough in relating this experience to Lady Waldegrave. Exhibition visitors stop to read this translated letter in its entirety. There is so little documentation on Tissot that it is as if he finally has a voice; otherwise, his work must speak for itself. But this exhibition, with its new works by Tissot, gives him a chance to do that.

Passing through the second gallery, which refreshes the mood of the exhibition with its sky blue walls, I found my gold mine of Tissot’s oils in the spacious third room, where the tan walls come alive with his colors.

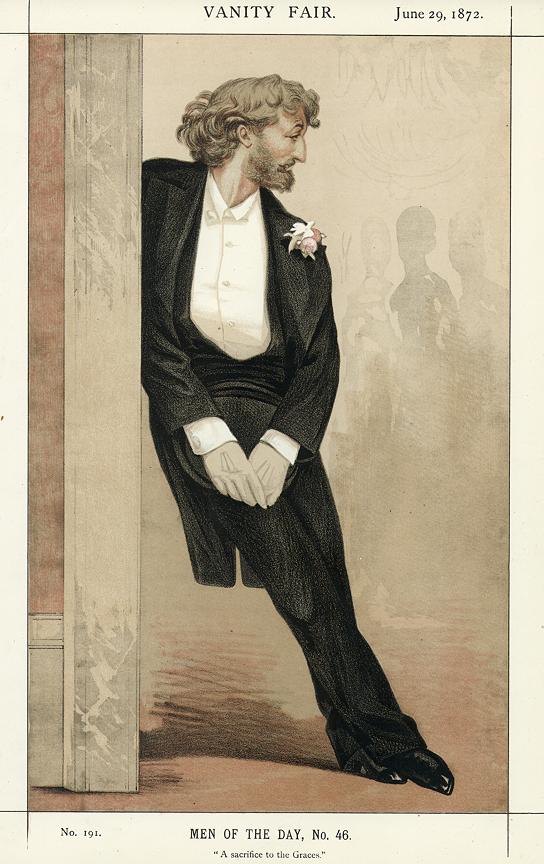

First, take a look at the smaller items that rarely (if ever) have been displayed in public. Here, you will find Tissot’s sketch of the handsome young Bowles, used as an illustration in The Defence of Paris; narrated as it was seen, published in London in 1871, Bowles’ eyewitness account as a special correspondent for The Morning Post. (Incidentally, this book is a great read, as Bowles was terribly witty and writes with a startlingly unperturbed and ironic tone.)

For additional information on the relationship between Tissot and Bowles, see my posts:

1869: Tissot meets “the irresistible” Tommy Bowles, founder of British Vanity Fair

James Tissot & Tommy Bowles Brave the Siege Together: October 1870

Tissot’s graphite drawing, A Cantinière of the National Guard (1870-71), is much more interesting than the engraving of it used as an illustration in Bowles’ book. A cantinière, the exhibition text explains, was “something like a nurse and a sutler (supplier of provisions) accompanying the troops – cantinières also took up arms on many occasions, playing an increasingly important role in the siege.”

![portrait-of-m-b]()

Portrait of Mrs. B (Mrs. Thomas Gibson Bowles, 1876), by James Tissot. (Photo: Wikipaintings.org)

Don’t miss Tissot’s etching of Bowle’s wife, Portrait of Mrs. B (1876). Tommy Bowles was the illegitimate son of Thomas Milner Gibson and a servant, Susannah Bowles. Jessica Evans-Gordon, daughter of Major-General C. G. Evans Gordon, Governor of Netley Hospital, married Bowles in December 1875 and died at 35 in 1887, having borne him four children. Though Tommy Bowles was quite high-spirited in his youth, he was devoted to the prudent Jessie, so very sober in this image. After her death, he wrote “So bright and joyous, so gentle and gracious a spirit as hers…still more rarely has been so ordered by a sense of duty. She was as near perfect wife and mother as may be.”

Then, indulge in the visual feast of some of Tissot’s best, and most well-known, oil paintings – brimming with his wit, flair, psychological insight and unparalleled ability to capture moments of Victorian life and transport us to his world.

![photo 1 (3)]()

Captain Frederick Gustavus Burnaby (1870), by James Tissot. Oil on panel, 50 by 61 cm. National Portrait Gallery, London. (Photo by Lucy Paquette, 2014).

![4-napoleon_iii_vanity_fair_1869-09-04-public-domain-image]()

Napoléon III, by Tissot (Photo: Wiki)

Tissot, 33 when he painted this small picture of the debonair Captain Frederick Gustavus Burnaby (1870). Tissot owned a villa on the most prestigious avenue in Paris (now avenue Foch), and he occasionally supplied his British friend Tommy Bowles with caricatures of prominent men for Vanity Fair, Tommy’s new Society magazine which had made its début in London in 1868. (The exhibition features Tissot’s caricature, Napoléon III, Emperor of France, published in Vanity Fair on September 4, 1869.) One of Tommy Bowles’ closest friends was the dashing Gus Burnaby (Frederick Gustavus Burnaby, 1842 – 1885), a captain in the privileged Royal Horse Guards, the cavalry regiment that protected the monarch. Gus, a member of the Prince of Wales’ set, had suggested the name, Vanity Fair, lent Bowles half of the necessary £200 in start-up funding, and then volunteered to go to Spain to chronicle his adventures for the satirical magazine. All Burnaby’s letters, which were first published on December 19, 1868 and continued through 1869, were titled “Out of Bounds” and signed “Convalescent” (he suffered intermittent bouts of digestive ailments and depression throughout his life). Tommy Bowles was 29 when he commissioned Tissot to paint Burnaby’s portrait.

[To learn about another portrait commission from Bowles to Tissot (not included in the exhibition), see my post: James Tissot’s “Miss Sydney Milner-Gibson” (c. 1872).]

![BAG4346]()

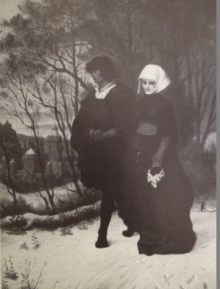

Les Adieux (The Farewells) 1871, by James Tissot, oil on canvas, 100.3 by 62.5 cm. Bristol Museum and Art Gallery. Photo courtesy of The Bridgeman Art Library for use in The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot, by Lucy Paquette © 2012

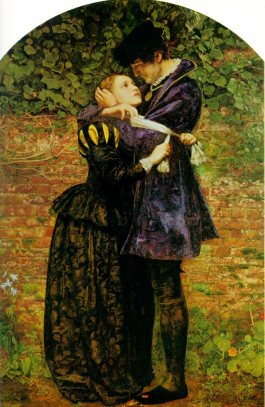

![huguenot_lovers_on_st-_bartholomew27s_day]()

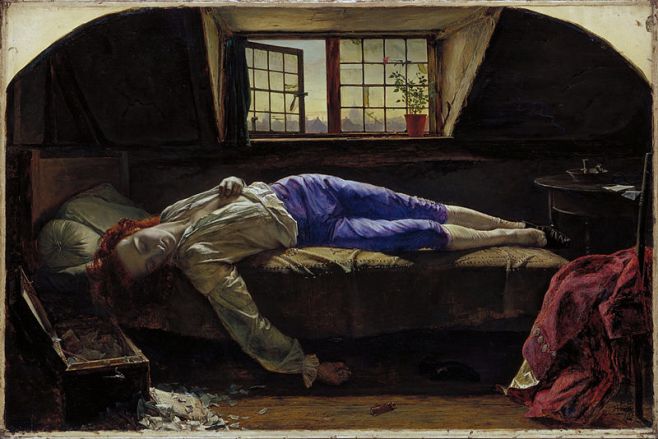

A Huguenot (1851-52), by J.E. Millais. (Photo: Wiki)

James Tissot fled Paris in June, 1871. He arrived in London with less than one hundred francs, and with the help of a handful of friends, he proceeded to rebuild his career.

In 1872, Tissot exhibited Les Adieux (The Farewells, 1871) at the Royal Academy. A sentimental costume piece calculated to appeal to the British public, it is displayed adjacent to J.E. Millais’ A Huguenot (1851-52), which it greatly resembles. [See my post, Was James Tissot a Plagiarist?]

Les Adieux was reproduced as a steel engraving by John Ballin and published by Pilgeram and Lefèvre in 1873 – an indication of its popularity.

This exhibition is a great opportunity to see this painting.

![Too Early 2]()

Too Early (1873), by James Tissot. Oil on canvas, 71 by 102 cm. Guildhall Art Gallery. (Photo by Lucy Paquette, 2014)

James Tissot exhibited Too Early at the Royal Academy in 1873, where it was his first big success after moving to London from Paris two years previously. According to his friend, the painter Louise Jopling (1843 – 1933), Too Early “made a great sensation…It was a new departure in Art, this witty representation of modern life.” Too Early was purchased by London art dealer William Agnew (1825 – 1910) – who specialized in “high-class modern paintings” – and sold in March, 1873 (before its exhibition at the Royal Academy that year) to Charles Gassiot for £1,155. Gassiot (1826 – 1902) was a London wine merchant and art patron who, with his wife Georgiana, donated a number of his paintings to the Guildhall Art Gallery, London, including Too Early. For more on this painting, see my post, A Closer Look at Tissot’s “Too Early”.

![londonvisitors_james_tissot_1874]()

London Visitors (c. 1874), by James Tissot. Oil on canvas, 86.3 by 63.5 cm. Milwaukee Art Museum. (Photo: Wikipedia)

According to interesting new research by Tissot scholar Krystyna Matyjaszkiewicz, this painting is not a smaller replica of London Visitors in the collection of the Toledo Museum of Art, as formerly believed. Mrs. Matyjaszkiewicz has learned from records in the National Gallery Archive that the smaller painting was completed several months before the other. First called The Portico, the picture in this exhibition was sold by Thomas Agnew & Sons as Country Cousins. This is a rare opportunity to see London Visitors up close.

![23-limperatrice_eugenie_et_son_fils_-_1878_-_james_tissot-public-domain-image]()

The Empress Eugénie and the Prince Impérial in the Grounds at Camden Place, Chislehurst (c. 1874), by James Tissot. Oil on canvas, 105 by 150 cm. Musée Nationale du Château de Compiègne. (Photo: Wikimedia.org)

The Empress Eugénie and the Prince Impérial in the Grounds at Camden Place, Chislehurst (c. 1874) depicts the exiled French Empress (1826 – 1920), living outside London after the collapse of the Second Empire, and her son, Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte (1856 – 1879), who would be killed at age 23, in the Zulu War. The only child of Napoléon III of France, he was accepted to the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich, in 1872 and is pictured in his uniform as a cadet. The Empress is in her first year of mourning following the death of her husband in January, 1873, after surgery to remove bladder stones.

Alison McQueen, in Empress Eugénie and the Arts: Politics and Visual Culture in the Nineteenth Century (Routledge, 2017), states that the picture was commissioned by the Empress and adds, “The wicker chairs and carpet reappear in A Convalescent (c. 1875-76), which further suggests Tissot constructed these scenes in his studio and was not recording mother and son from life studies executed on the property at Camden.”

According to Krystyna Matyjaszkiewicz, who wrote the exhibition catalogue entry, he painted this double portrait of the exiled French royals for the 1875 Royal Academy exhibition, but it was rejected, along with two others (while yet two others, Hush! (The Concert) and The Bunch of Lilacs, were accepted.)

The painting was purchased by Kaye Knowles, Esq. (1835-1886), a client of London art dealer Algernon Moses Marsden [1848-1920, see Who was Algernon Moses Marsden?]. Knowles, whose vast wealth came from shares in his family’s Lancashire coal mining business, owned a large collection of paintings by contemporary artists, including three other oils by Tissot.

![hush-the-concert]()

Hush! (The Concert, 1875), by James Tissot. Oil on canvas, 73.7 by 112.2 cm. Manchester Art Gallery. (Photo: Wikiart.org)

James Tissot displayed Hush! (The Concert) at the Royal Academy exhibition in 1875, at the height of his success in London. It depicts a crowded Kensington salon, said to have been hosted by Lord and Lady Coope, which features a performer believed to be Moravian violinist Wilma Neruda (1838 – 1911). Though Tissot received an invitation to this soirée, he was not given permission to make portraits of any of the guests. Acquired by the Manchester Art Gallery in 1933, Hush! is a lovely picture that, on closer inspection, is quite witty. For more on this painting, see my post, A Closer Look at Tissot’s “Hush! (The Concert)”.

![www.jamestissot.org, The-Garden]()

View of the Garden at 17 Grove End Road (c. 1882), by James Tissot. Oil on canvas, 27 by 21 cm. Geffrye Museum of the Home. Courtesy http://www.jamestissot.org

By 1873, two years after Tissot arrived in London, he had established himself in a Queen Anne-style villa at 17 (now 44), Grove End Road, St. John’s Wood. He designed his garden as a blend of English-style flower beds and plantings familiar to him from French parks. Gravel paths led to kitchen gardens and greenhouses for flowers, fruit and vegetables. View of the Garden at 17 Grove End Road (c. 1874-1882) is unusual in that Tissot seldom depicted a landscape that was not a background for figures. Previously in a private collection, View of the Garden was sold to Agnew’s at Sotheby’s, London in 2000 and purchased by the Geffrye in 2004.

![portrait-of-miss-lloyd]()

Summer (A Portrait, 1876), by James Tissot. Oil on canvas, 91.4 by 50.8 cm. Tate.

Summer (A Portrait), 1876 is radiant and has benefited from recent cleaning. The woman’s white muslin gown, with its lemon-yellow stain bows, shimmers, and details such as her ring, and the designs on the blue-green curtains, pull you into the scene.

This painting was exhibited by Tissot at the new Grosvenor Gallery, London, from May to June 1877 as A Portrait.

![The Gallery of HMS Calcutta (Portsmouth) c.1876 by James Tissot 1836-1902]()

- The Gallery of HMS Calcutta (Portsmouth), c.1876, by James Tissot. Oil on canvas, 68.6 by 91.8 cm. Tate.

Though I’ve visited the Tate numerous times, this is the first time I’ve seen The Gallery of HMS Calcutta in person. What can I say – it’s one of Tissot’s masterpieces, and I was rooted to the spot studying it, as was everyone around me. You just cannot take your eyes off the gowns, the bows, the faces, the curvaceous wrought-iron railing, the way Tissot painted the caned chairs, the curves of the windows, the rigging of the ships in the distance…it’s an all-you-can-eat buffet for the eyes. Tissot exhibited it at the Grosvenor Gallery in 1877 to rather cutting reviews. Go see it while you can, and form your own opinion.

Also in this third gallery are a few etchings and photographs of Kathleen Newton (1854 –1882), Tissot’s young mistress and muse from about 1876 until her death from tuberculosis six years later. An idea for a future exhibition would be a display of the numerous images of Mrs. Newton that Tissot produced, with all known photographs of her and of the two of them together, but this exhibition is not about their relationship.

Keep walking, because in a further gallery showcasing images of “British Sports, Crowds, and Parks,” you will find more of Tissot’s paintings.

![James_Tissot_-_Holyday]()

Holyday (c. 1876), by James Tissot. Oil on canvas, 76.2 by 99.4 cm. Tate.

In Holyday (c. 1876), Tissot painted members of the famous I Zingari cricket club (which still exists, and is one of the oldest amateur cricket clubs) in their distinctive black, red and gold caps in his garden at 17 Grove End Road, St. John’s Wood, which was only a few hundred yards from Lord’s cricket ground. Holyday was owned by James Taylor, who lent it for exhibition at the Grosvenor Gallery in London from May to June, 1877. The painting was purchased by the Tate in 1928.

I’ve long wanted to see Holyday up close, and I found it so intriguing. The painting includes a woman I’d never noticed in print or digital images – she is indicated only by her white straw bonnet, behind the man leaning against a tree on the far right of the picture. And the addition of the two other women on the picnic blanket is indicated in the bottom left corner by their skirts, one black-and-white striped, one brown, with the soles of her shoes peeking out behind her knife-pleated hemline. There’s also a little girl, whom I’ve never noticed, sitting at the feet of the old lady in the wicker chair. This is such a merry picture! It makes you want to join this lively group for a cup of tea and a slice of cake.

![Ball on Shipboard]()

The Ball on Shipboard (c. 1874), by James Tissot. Tate. (Photo: Lucy Paquette, 2014)

The Ball on Shipboard (1874) is a large, dramatic, detailed painting that invites speculation: an enigmatic image as precise as a photograph but which evades precise meaning. You find yourself transfixed as you try to puzzle it out.

In the center are two women wearing matching blue-and-white yachting gowns. Scholars have written that Tissot had a fixation with twins, though in the 2013 blockbuster exhibition, “Impressionism, Fashion, and Modernity” exhibition curator Gloria Groom of The Art Institute of Chicago asserted that in The Ball on Shipboard, Tissot was satirizing the rise of ready-to-wear fashion (and, of course, the vulgar social climbing efforts of the nouveaux riches). This is not Tissot’s only painting of women wearing identical ensembles: see In the Conservatory (1875-76, also known as The Rivals). In fact, according to my own research, Alexandra, Princess of Wales (1844 – 1925) and her sister, at that time Grand Duchess Maria Feodorovna of Russia. (1847 –1928, formerly Princess Dagmar of Denmark), were very close and had a habit of wearing identical ensembles when they were together, setting off a general fad for “double-dressing.” When the Grand Duchess and her husband the Tsarevich visited London in the summer of 1873, the two sisters wore the same costumes on at least thirteen occasions.

In “Impressionists in London,” it is asserted the pair of women in the center of The Ball on Shipboard actually are the Princess of Wales and Maria Feodorovna of Russia, and the occasion an afternoon dance held on the royal naval frigate HMS Ariadne on August 12, 1873, according to research by Krystyna Matyjaszkiewicz.

![Ball, detail 3]() I’m not on board with this theory. Making royal portraits on, or of, such an occasion would have required that Tissot receive official permission. This was unlikely, since he was a foreigner and regarded with suspicion for his participation, real or rumored, in the Paris Commune of 1871. He was not granted permission to make portraits of any of the guests at Lord and Lady Coopes’ salon for Hush! (The Concert, 1873). Had he received such permission from the royal family, it would have been common knowledge at the time. But instead of recognizing this as a royal dance, one reviewer wrote, “The girls who are spread about in every attitude are evidently the ‘high life below stairs’ of the port, who have borrowed their mistresses’ dresses for the nonce,” and another objected to the unseemly amount of cleavage revealed by the women wearing the blue and green day dresses (left of center). Another critic found in the picture, “no pretty women, but a set of showy rather than elegant costumes, some few graceful, but more ungraceful attitudes, and not a lady in a score of female figures,” and another found it “garish and almost repellent.” While Tissot’s contemporaries (but interestingly, not Tissot himself) identified the setting as the yearly regatta at Cowes, on the Isle of Wight, no one at the time considered this a painting of a royal event. It also makes no sense that Tissot would have made portraits of these two royal women in their matching nautical gowns – and painted the same gown in Reading the News (c. 1874). It makes more sense that Tissot seized on the concept of a regatta scene while showcasing his skill at painting women’s fashions during the craze for double-dressing, also celebrated by the pairs of women in blue and in green in the center background.

I’m not on board with this theory. Making royal portraits on, or of, such an occasion would have required that Tissot receive official permission. This was unlikely, since he was a foreigner and regarded with suspicion for his participation, real or rumored, in the Paris Commune of 1871. He was not granted permission to make portraits of any of the guests at Lord and Lady Coopes’ salon for Hush! (The Concert, 1873). Had he received such permission from the royal family, it would have been common knowledge at the time. But instead of recognizing this as a royal dance, one reviewer wrote, “The girls who are spread about in every attitude are evidently the ‘high life below stairs’ of the port, who have borrowed their mistresses’ dresses for the nonce,” and another objected to the unseemly amount of cleavage revealed by the women wearing the blue and green day dresses (left of center). Another critic found in the picture, “no pretty women, but a set of showy rather than elegant costumes, some few graceful, but more ungraceful attitudes, and not a lady in a score of female figures,” and another found it “garish and almost repellent.” While Tissot’s contemporaries (but interestingly, not Tissot himself) identified the setting as the yearly regatta at Cowes, on the Isle of Wight, no one at the time considered this a painting of a royal event. It also makes no sense that Tissot would have made portraits of these two royal women in their matching nautical gowns – and painted the same gown in Reading the News (c. 1874). It makes more sense that Tissot seized on the concept of a regatta scene while showcasing his skill at painting women’s fashions during the craze for double-dressing, also celebrated by the pairs of women in blue and in green in the center background.

![Ball, detail 2]() If The Ball on Shipboard had featured a double portrait of royalty, it was not purchased by anyone connected to the royal family. London art dealer William Agnew (1825 – 1910) – who specialized in “high-class modern paintings” – purchased The Ball on Shipboard from Tissot that year and sold it to Hilton Philipson (1834 – 1904), a solicitor and colliery owner living at Tynemouth. It was later owned by equine painter Alfred Munnings (1878 – 1959), who presented it to the Tate in 1937.

If The Ball on Shipboard had featured a double portrait of royalty, it was not purchased by anyone connected to the royal family. London art dealer William Agnew (1825 – 1910) – who specialized in “high-class modern paintings” – purchased The Ball on Shipboard from Tissot that year and sold it to Hilton Philipson (1834 – 1904), a solicitor and colliery owner living at Tynemouth. It was later owned by equine painter Alfred Munnings (1878 – 1959), who presented it to the Tate in 1937.

![WAK41966]()

On the Thames (1876), by James Tissot. Oil on canvas, 74.8 by 110 cm. The Hepworth Wakefield. Courtesy of The Bridgeman Art Library for use in “The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot” by Lucy Paquette © 2012.

Remember to look behind the partition at the back of the room for On the Thames (c. 1876), a masterpiece of texture: wood, wicker, fabric, fur, leather, metal, water, and mist. Take a long, close look at the picnic hamper.

Tissot displayed this picture as The Thames at the Royal Academy exhibition in 1876, the year he painted it. It was attacked by reviewers for The Times, the Athenaeum, the Spectator and the Graphic as depicting a subject they considered thoroughly unBritish – prostitution. What else would the Victorians think of a painting of a rakish officer in a boat with two attractive women and a picnic hamper with three bottles of champagne? The women were perceived as “undeniably Parisian ladies,” and the picture itself, “More French, shall we say, than English?”

This criticism prompted Tissot to paint the more innocent Portsmouth Dockyard (How Happy I Could be with Either!, c. 1877). A much smaller picture than On the Thames, it is displayed earlier in the exhibition, but I wish the two had been displayed side-by-side.

![Portsmouth Dockyard circa 1877 by James Tissot 1836-1902]()

Portsmouth Dockyard (c. 1877), by James Tissot. Oil on canvas, 38.1 by 54.6 cm. Tate.

By this time, you will need to seek seating and sustenance, but your brain will be fully sparked. The details in all Tissot’s paintings are extraordinary – really enthralling to observe close-up. To learn more about a number of the Tissot oils in the show, see my posts:

Tissot in the U.K.: London, at the Tate

Tissot in the U.K.: London, at The Geffrye & the Guildhall

Tissot in the U.K.: Northern England.

There is a great deal more to “Impressionists in London” than James Tissot, of course, and more than one visit is necessary to take in works by Monet – including a group of his Houses of Parliament series – Pissarro, Sisley, Alphonse Legros, sculptor Aimé-Jules Dalou, André Derain, and others. But if you love Tissot’s work and want to learn more about him, see this show if you can, and let me know what you think.

“The EY Exhibition: Impressionists in London, French Artists in Exile (1870 – 1904),” November 2, 2017 – May 7, 2018.

Tate Britain

See “James Tissot, the Englishman,” by Cyrille Sciama, Curator of the 19th century collections at the Musée d’arts de Nantes, in the exhibition catalogue.

My gratitude to Alexandra Epps and Dr. Caroline Corbeau-Parsons

for their kindness during my visits to the exhibition.

© 2018 Lucy Paquette. All rights reserved.

View my video, “The Strange Career of James Tissot” (Length: 2:33 minutes).

Related posts:

A spotlight on Tissot at the Met’s “Impressionism, Fashion, and Modernity”

James Tissot is now in Italy!

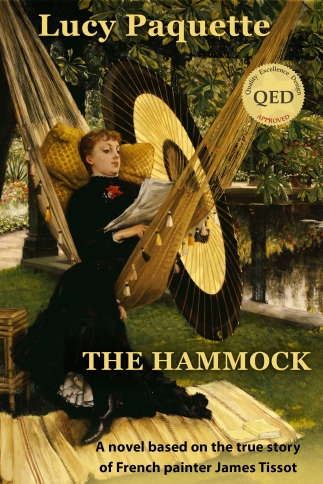

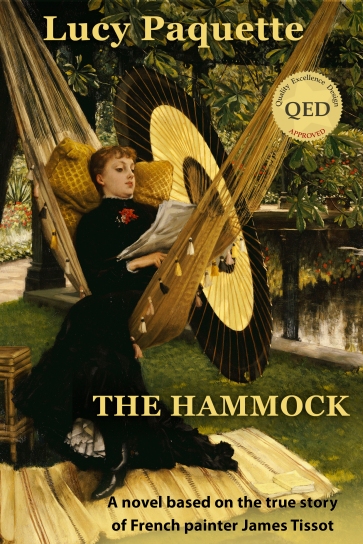

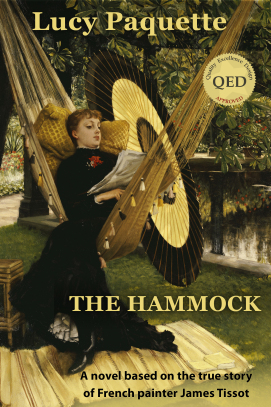

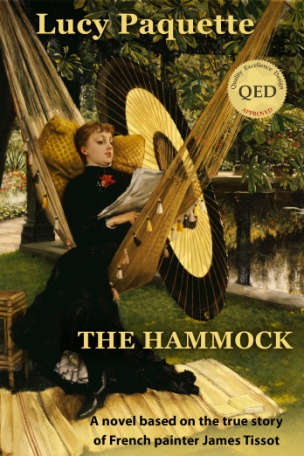

![CH377762]() The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot, brings Tissot’s world from 1870 to 1879 alive in a story of war, art, Society glamour, love, scandal, and tragedy.

The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot, brings Tissot’s world from 1870 to 1879 alive in a story of war, art, Society glamour, love, scandal, and tragedy.

Illustrated with 17 stunning, high-resolution fine art images in full color

Courtesy of The Bridgeman Art Library

(295 pages; ISBN (ePub): 978-0-615-68267-9).

See http://www.amazon.com/dp/B009P5RYVE.

NOTE: If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download free Kindle reading apps for PCs, Smartphones, tablets, and the Kindle Cloud Reader to read The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot. Read reviews.

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download free Kindle reading apps for PCs, Smartphones, tablets, and the Kindle Cloud Reader to read The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot. Read reviews.

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download free Kindle reading apps for PCs, Smartphones, tablets, and the Kindle Cloud Reader to read The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot. Read reviews. We know so little of James Tissot (1836 – 1902) outside of his work; his personal papers were destroyed, and he had no disciples to carry on and burnish his reputation.

We know so little of James Tissot (1836 – 1902) outside of his work; his personal papers were destroyed, and he had no disciples to carry on and burnish his reputation.

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download

In Birmingham, where the industrial steam engine was invented and which became a manufacturing powerhouse, the architecture was grander than in Nottingham. Queen Victoria granted Birmingham city status in 1889, and the vibrant center of the second most populous city in Britain is now under the gaze of the bronze monument to her in Victoria Square.

In Birmingham, where the industrial steam engine was invented and which became a manufacturing powerhouse, the architecture was grander than in Nottingham. Queen Victoria granted Birmingham city status in 1889, and the vibrant center of the second most populous city in Britain is now under the gaze of the bronze monument to her in Victoria Square.

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download

Fashion historian James Laver (1899 – 1975), in his 1936 biography of James Tissot, claimed that Tissot had received an invitation to the Coopes’ at which Madame Neruda performed, but that he did not have permission to make portraits of any of the guests. Instead, he painted types, some based on models he used in other paintings, including the old gentleman with the white whiskers in the left corner who also appears in Reading the News (1874), in the center of The Ball on Shipboard (c. 1874), and in The Warrior’s Daughter (A Convalescent, c. 1878). The older, white-haired woman on the right also appears in A Convalescent (c. 1876) and Holyday (c 1876).

Fashion historian James Laver (1899 – 1975), in his 1936 biography of James Tissot, claimed that Tissot had received an invitation to the Coopes’ at which Madame Neruda performed, but that he did not have permission to make portraits of any of the guests. Instead, he painted types, some based on models he used in other paintings, including the old gentleman with the white whiskers in the left corner who also appears in Reading the News (1874), in the center of The Ball on Shipboard (c. 1874), and in The Warrior’s Daughter (A Convalescent, c. 1878). The older, white-haired woman on the right also appears in A Convalescent (c. 1876) and Holyday (c 1876). If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download

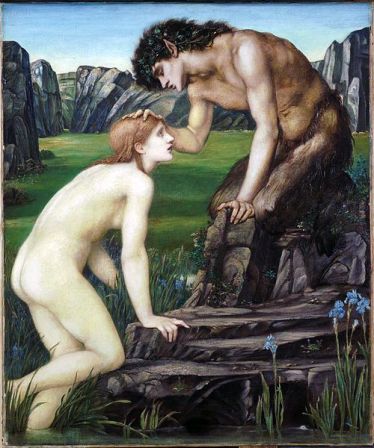

Tissot enrolled at the Académie des Beaux-Arts on March 9, 1857, though there is little documentation on the regularity of his attendance at classes, which included mathematics, anatomy and drawing, but not painting. He studied painting independently under Jean-Hippolyte Flandrin (1809 – 1864) and Louis Lamothe (1822 – 1869), both of whom had been students of the great Neoclassical painter Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780 – 1867) and taught his principles. Flandrin, who had earned a first-class medal at the Paris Exhibition of 1855, was a prolific artist, and he increasingly directed his students to his former student, Louis Lamothe. Lamothe was a clear and precise draftsman with a passion for detail, and Tissot acknowledged that his own work was significantly influenced by Lamothe’s instruction.

Tissot enrolled at the Académie des Beaux-Arts on March 9, 1857, though there is little documentation on the regularity of his attendance at classes, which included mathematics, anatomy and drawing, but not painting. He studied painting independently under Jean-Hippolyte Flandrin (1809 – 1864) and Louis Lamothe (1822 – 1869), both of whom had been students of the great Neoclassical painter Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780 – 1867) and taught his principles. Flandrin, who had earned a first-class medal at the Paris Exhibition of 1855, was a prolific artist, and he increasingly directed his students to his former student, Louis Lamothe. Lamothe was a clear and precise draftsman with a passion for detail, and Tissot acknowledged that his own work was significantly influenced by Lamothe’s instruction.

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download  The exhibition is huge, and the galleries were crowded on each of the two days I visited. There is a great deal of beauty on display, but it’s also a very ambitious, cerebral show, so you have to pace yourself.

The exhibition is huge, and the galleries were crowded on each of the two days I visited. There is a great deal of beauty on display, but it’s also a very ambitious, cerebral show, so you have to pace yourself.

I’m not on board with this theory. Making royal portraits on, or of, such an occasion would have required that Tissot receive official permission. This was unlikely, since he was a foreigner and regarded with suspicion for his participation, real or rumored, in the Paris Commune of 1871. He was not granted permission to make portraits of any of the guests at Lord and Lady Coopes’ salon for Hush! (The Concert, 1873). Had he received such permission from the royal family, it would have been common knowledge at the time. But instead of recognizing this as a royal dance, one reviewer wrote, “The girls who are spread about in every attitude are evidently the ‘high life below stairs’ of the port, who have borrowed their mistresses’ dresses for the nonce,” and another objected to the unseemly amount of cleavage revealed by the women wearing the blue and green day dresses (left of center). Another critic found in the picture, “no pretty women, but a set of showy rather than elegant costumes, some few graceful, but more ungraceful attitudes, and not a lady in a score of female figures,” and another found it “garish and almost repellent.” While Tissot’s contemporaries (but interestingly, not Tissot himself) identified the setting as the yearly regatta at Cowes, on the Isle of Wight, no one at the time considered this a painting of a royal event. It also makes no sense that Tissot would have made portraits of these two royal women in their matching nautical gowns – and painted the same gown in Reading the News (c. 1874). It makes more sense that Tissot seized on the concept of a regatta scene while showcasing his skill at painting women’s fashions during the craze for double-dressing, also celebrated by the pairs of women in blue and in green in the center background.

I’m not on board with this theory. Making royal portraits on, or of, such an occasion would have required that Tissot receive official permission. This was unlikely, since he was a foreigner and regarded with suspicion for his participation, real or rumored, in the Paris Commune of 1871. He was not granted permission to make portraits of any of the guests at Lord and Lady Coopes’ salon for Hush! (The Concert, 1873). Had he received such permission from the royal family, it would have been common knowledge at the time. But instead of recognizing this as a royal dance, one reviewer wrote, “The girls who are spread about in every attitude are evidently the ‘high life below stairs’ of the port, who have borrowed their mistresses’ dresses for the nonce,” and another objected to the unseemly amount of cleavage revealed by the women wearing the blue and green day dresses (left of center). Another critic found in the picture, “no pretty women, but a set of showy rather than elegant costumes, some few graceful, but more ungraceful attitudes, and not a lady in a score of female figures,” and another found it “garish and almost repellent.” While Tissot’s contemporaries (but interestingly, not Tissot himself) identified the setting as the yearly regatta at Cowes, on the Isle of Wight, no one at the time considered this a painting of a royal event. It also makes no sense that Tissot would have made portraits of these two royal women in their matching nautical gowns – and painted the same gown in Reading the News (c. 1874). It makes more sense that Tissot seized on the concept of a regatta scene while showcasing his skill at painting women’s fashions during the craze for double-dressing, also celebrated by the pairs of women in blue and in green in the center background. If The Ball on Shipboard had featured a double portrait of royalty, it was not purchased by anyone connected to the royal family. London art dealer William Agnew (1825 – 1910) – who specialized in “high-class modern paintings” – purchased The Ball on Shipboard from Tissot that year and sold it to Hilton Philipson (1834 – 1904), a solicitor and colliery owner living at Tynemouth. It was later owned by equine painter Alfred Munnings (1878 – 1959), who presented it to the Tate in 1937.

If The Ball on Shipboard had featured a double portrait of royalty, it was not purchased by anyone connected to the royal family. London art dealer William Agnew (1825 – 1910) – who specialized in “high-class modern paintings” – purchased The Ball on Shipboard from Tissot that year and sold it to Hilton Philipson (1834 – 1904), a solicitor and colliery owner living at Tynemouth. It was later owned by equine painter Alfred Munnings (1878 – 1959), who presented it to the Tate in 1937.

The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot, brings Tissot’s world from 1870 to 1879 alive in a story of war, art, Society glamour, love, scandal, and tragedy.

The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot, brings Tissot’s world from 1870 to 1879 alive in a story of war, art, Society glamour, love, scandal, and tragedy. In Quarrelling, which Tissot exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1876, a stylish couple stand in uncomfortable silence on opposite sides of one of the cast-iron columns in the graceful, curved colonnade that Tissot added to his garden at 17 (now 44), Grove End Road, St. John’s Wood, around 1875. Copied from the colonnade in Parc Monceau in Paris, it became the backdrop for a number of Tissot’s paintings in the next few years.

In Quarrelling, which Tissot exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1876, a stylish couple stand in uncomfortable silence on opposite sides of one of the cast-iron columns in the graceful, curved colonnade that Tissot added to his garden at 17 (now 44), Grove End Road, St. John’s Wood, around 1875. Copied from the colonnade in Parc Monceau in Paris, it became the backdrop for a number of Tissot’s paintings in the next few years.

The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot, brings Tissot’s world from 1870 to 1879 alive in a story of war, art, Society glamour, love, scandal, and tragedy.

The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot, brings Tissot’s world from 1870 to 1879 alive in a story of war, art, Society glamour, love, scandal, and tragedy. Marsden was a witty and engaging gambler, bankrupt and rogue who foisted his debts on his father and deserted his wife and ten children. When his father died in 1884, he disinherited his son but provided legacies for his abandoned family members. In 1901, bankrupt for at least the third time, Algernon, at age 54, fled to the United States with another woman.

Marsden was a witty and engaging gambler, bankrupt and rogue who foisted his debts on his father and deserted his wife and ten children. When his father died in 1884, he disinherited his son but provided legacies for his abandoned family members. In 1901, bankrupt for at least the third time, Algernon, at age 54, fled to the United States with another woman.

The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot, brings Tissot’s world from 1870 to 1879 alive in a story of war, art, Society glamour, love, scandal, and tragedy.

The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot, brings Tissot’s world from 1870 to 1879 alive in a story of war, art, Society glamour, love, scandal, and tragedy.

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download

The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot, brings Tissot’s world from 1870 to 1879 alive in a story of war, art, Society glamour, love, scandal, and tragedy.

The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot, brings Tissot’s world from 1870 to 1879 alive in a story of war, art, Society glamour, love, scandal, and tragedy.

f you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download

f you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download

Tea

Tea

The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot, brings Tissot’s world from 1870 to 1879 alive in a story of war, art, Society glamour, love, scandal, and tragedy.

The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot, brings Tissot’s world from 1870 to 1879 alive in a story of war, art, Society glamour, love, scandal, and tragedy. In these past six years, French painter James Tissot and his work have become increasingly familiar to the public.

In these past six years, French painter James Tissot and his work have become increasingly familiar to the public. After Tissot’s death in 1902, interest in his work declined until Victorian art regained popularity in the 1960s.

After Tissot’s death in 1902, interest in his work declined until Victorian art regained popularity in the 1960s. Much of Tissot’s work is privately owned (for instance, see

Much of Tissot’s work is privately owned (for instance, see

Writing this blog is a labor of love, a way to share some of my research on James Tissot’s life and work, and is limited only by the necessity of avoiding copyrighted images. Since I began six years ago, more high resolution, Open Access images have been made available, notably through The Getty Museum and The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Writing this blog is a labor of love, a way to share some of my research on James Tissot’s life and work, and is limited only by the necessity of avoiding copyrighted images. Since I began six years ago, more high resolution, Open Access images have been made available, notably through The Getty Museum and The Metropolitan Museum of Art. While conducting research for the blog, I’ve enjoyed a private tour of Tissot’s former home in London (now a family residence; see

While conducting research for the blog, I’ve enjoyed a private tour of Tissot’s former home in London (now a family residence; see  I’ve visited museums and galleries, large and small, in the U.S., Canada, the U.K., and France, studying Tissot’s paintings, for my “A Closer Look” series, in which I share my (and my husband’s) photographs and experiences with you. Another series of articles explores Tissot’s work in various countries and regions within them; a subsequent series follows Tissot’s work and reputation in the decades between his death and the new millennium; another highlights masculine fashion in Tissot’s paintings; yet another focuses on various stages of Tissot’s work:

I’ve visited museums and galleries, large and small, in the U.S., Canada, the U.K., and France, studying Tissot’s paintings, for my “A Closer Look” series, in which I share my (and my husband’s) photographs and experiences with you. Another series of articles explores Tissot’s work in various countries and regions within them; a subsequent series follows Tissot’s work and reputation in the decades between his death and the new millennium; another highlights masculine fashion in Tissot’s paintings; yet another focuses on various stages of Tissot’s work: I’ve collected little-known items of interest about Tissot’s works, such as the near-destruction of one of his most beautiful images, Still on Top (c. 1874), in the collection of the Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki in New Zealand, in

I’ve collected little-known items of interest about Tissot’s works, such as the near-destruction of one of his most beautiful images, Still on Top (c. 1874), in the collection of the Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki in New Zealand, in  In other posts, I’ve presented little-known information about Tissot himself:

In other posts, I’ve presented little-known information about Tissot himself:  While I began my research on James Tissot in 2009, when drafting my novel, it’s been in the six years since I launched this blog that I’ve been contacted by individuals with unexpected, wonderful, documented facts to share related to James Tissot and his work, including biographical details of people he knew, information on his Paris villa, close-up photographs of some of Tissot’s works I have not been able to visit, a hot tip on an unannounced, temporary exhibition of three of his privately-owned masterpieces at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford last year, and the name of a celebrity owner* of one of his most recognizable paintings, as well as the gift of a scholarly work by a Tissot-loving museum curator I befriended through my blog. All of this spontaneous generosity is a remarkable feature of the support I’ve enjoyed.

While I began my research on James Tissot in 2009, when drafting my novel, it’s been in the six years since I launched this blog that I’ve been contacted by individuals with unexpected, wonderful, documented facts to share related to James Tissot and his work, including biographical details of people he knew, information on his Paris villa, close-up photographs of some of Tissot’s works I have not been able to visit, a hot tip on an unannounced, temporary exhibition of three of his privately-owned masterpieces at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford last year, and the name of a celebrity owner* of one of his most recognizable paintings, as well as the gift of a scholarly work by a Tissot-loving museum curator I befriended through my blog. All of this spontaneous generosity is a remarkable feature of the support I’ve enjoyed. So, a heartfelt thank you – to all of you who read my blog, and to my husband, who contributes such helpful images to it. Through it, I’ve met the loveliest people, was invited to serve as a guest blogger, a contributor to The Victorian Web, and recently was interviewed for an art podcast:

So, a heartfelt thank you – to all of you who read my blog, and to my husband, who contributes such helpful images to it. Through it, I’ve met the loveliest people, was invited to serve as a guest blogger, a contributor to The Victorian Web, and recently was interviewed for an art podcast: I have collected scholarly works on James Tissot, but they are largely biocritical studies: there is so little documentation on Tissot’s life that his work often has to speak for him. There are very few accounts of him by his contemporaries, and when his elderly, eccentric niece died in his château in eastern France in 1964, all his papers and drawings were auctioned off. My research centers on finding new information on his personality and actions, particularly during the Franco-Prussian War and Commune, using previously unconsidered primary sources. Tissot often seems to fall through the cracks of art history – as his work straddled French academic style, Realism, French Impressionism, and Victorian painting. He left France for eleven years, and while he was successful in London, he was not British. Tissot often is overlooked because he belongs to no category, really, but his own.

I have collected scholarly works on James Tissot, but they are largely biocritical studies: there is so little documentation on Tissot’s life that his work often has to speak for him. There are very few accounts of him by his contemporaries, and when his elderly, eccentric niece died in his château in eastern France in 1964, all his papers and drawings were auctioned off. My research centers on finding new information on his personality and actions, particularly during the Franco-Prussian War and Commune, using previously unconsidered primary sources. Tissot often seems to fall through the cracks of art history – as his work straddled French academic style, Realism, French Impressionism, and Victorian painting. He left France for eleven years, and while he was successful in London, he was not British. Tissot often is overlooked because he belongs to no category, really, but his own. James Tissot has a great story that hasn’t been told, and I encourage you to read

James Tissot has a great story that hasn’t been told, and I encourage you to read  The most recent retrospective of his work in North America, and the only one since the first in 1968 (in Rhode Island and Toronto), was James Tissot: Victorian Life/Modern Love, an exhibition that began at the Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, Connecticut, in 1999, and then traveled to the Musée du Québec, Canada, and the Albright-Knox Gallery, Buffalo, New York. But a major retrospective of his work will be held in Paris and San Francisco in 2020. I’m looking forward to it, and I hope to be invited to contribute some of the extensive new scholarship I have to offer on James Tissot’s life and work.

The most recent retrospective of his work in North America, and the only one since the first in 1968 (in Rhode Island and Toronto), was James Tissot: Victorian Life/Modern Love, an exhibition that began at the Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, Connecticut, in 1999, and then traveled to the Musée du Québec, Canada, and the Albright-Knox Gallery, Buffalo, New York. But a major retrospective of his work will be held in Paris and San Francisco in 2020. I’m looking forward to it, and I hope to be invited to contribute some of the extensive new scholarship I have to offer on James Tissot’s life and work. If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download

In

In

The perfectly placed dry brush strokes that Tissot used to define the volume of Gus Burnaby’s black leather boots and give them their astonishing gleam in

The perfectly placed dry brush strokes that Tissot used to define the volume of Gus Burnaby’s black leather boots and give them their astonishing gleam in

b

b

Tissot was masterful in his ability to paint the sheer fabrics of women’s attire. The Gallery of HMS Calcutta (1877) was one of Tissot’s exhibits at the new Grosvenor Gallery. In his review of this picture, the critic for The Spectator commented, “We would direct our readers’ attention to the painting of the flesh seen through the thin white muslin dresses, in this picture; manual dexterity could hardly achieve a greater triumph.” Regardless of Tissot’s skill with the brush, that compliment followed the acerbic observation, “That the ladies are ‘Parisienne,’ dressed in the height of the prevailing fashion, goes without saying, for M. Tissot, though he paints in England, has a thorough Parisian’s contempt for English dress and beauty, and the only time he attempted to paint English girls (in his picture of the ball-room at the Academy [i.e. Too Early, 1873]), he made them all hideous alike.” [See

Tissot was masterful in his ability to paint the sheer fabrics of women’s attire. The Gallery of HMS Calcutta (1877) was one of Tissot’s exhibits at the new Grosvenor Gallery. In his review of this picture, the critic for The Spectator commented, “We would direct our readers’ attention to the painting of the flesh seen through the thin white muslin dresses, in this picture; manual dexterity could hardly achieve a greater triumph.” Regardless of Tissot’s skill with the brush, that compliment followed the acerbic observation, “That the ladies are ‘Parisienne,’ dressed in the height of the prevailing fashion, goes without saying, for M. Tissot, though he paints in England, has a thorough Parisian’s contempt for English dress and beauty, and the only time he attempted to paint English girls (in his picture of the ball-room at the Academy [i.e. Too Early, 1873]), he made them all hideous alike.” [See

In Evening (Le Bal, 1878), the cascade of layered ruffles is a tour de force of Tissot’s ability to define precise, minute folds of fabric, shaded and highlighted and juxtaposed with contrasting trim in related hues. His lively brushwork lets us feel the volume, weight, and movement of that train.

In Evening (Le Bal, 1878), the cascade of layered ruffles is a tour de force of Tissot’s ability to define precise, minute folds of fabric, shaded and highlighted and juxtaposed with contrasting trim in related hues. His lively brushwork lets us feel the volume, weight, and movement of that train.

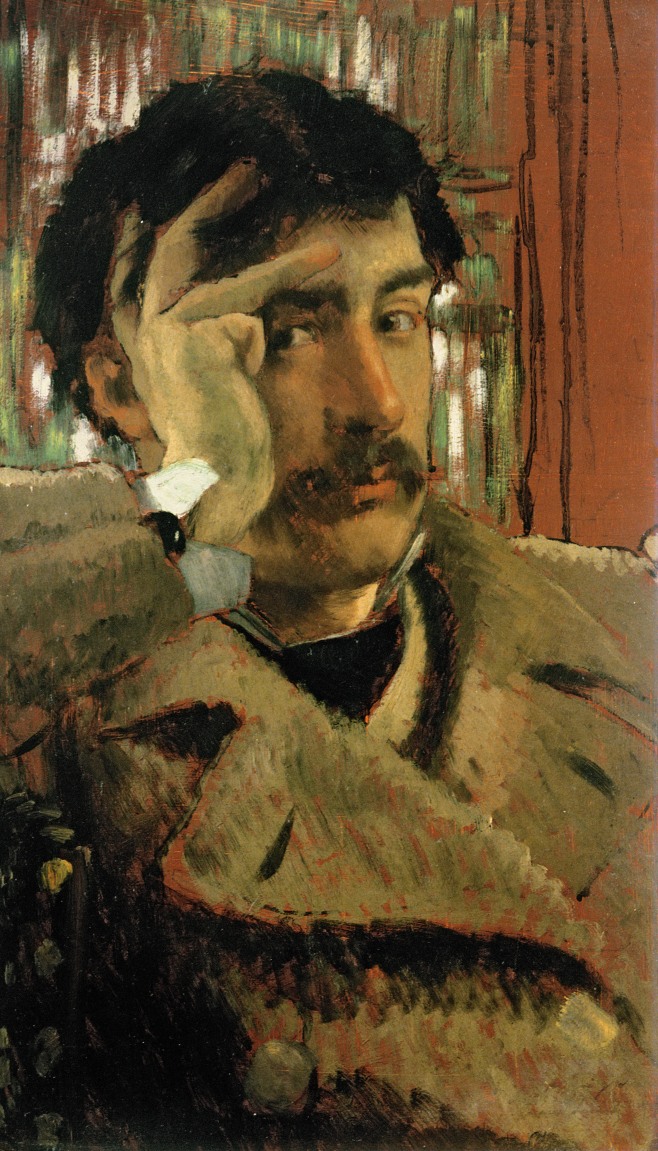

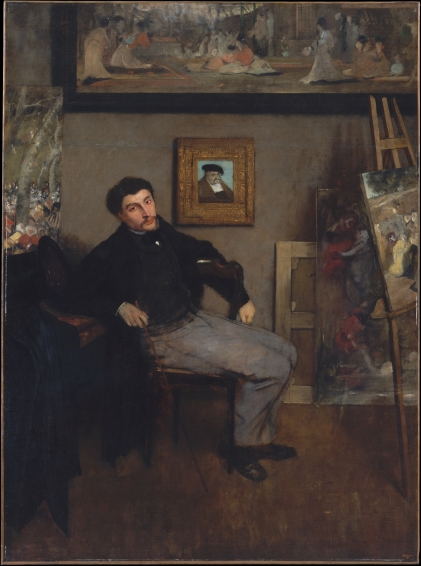

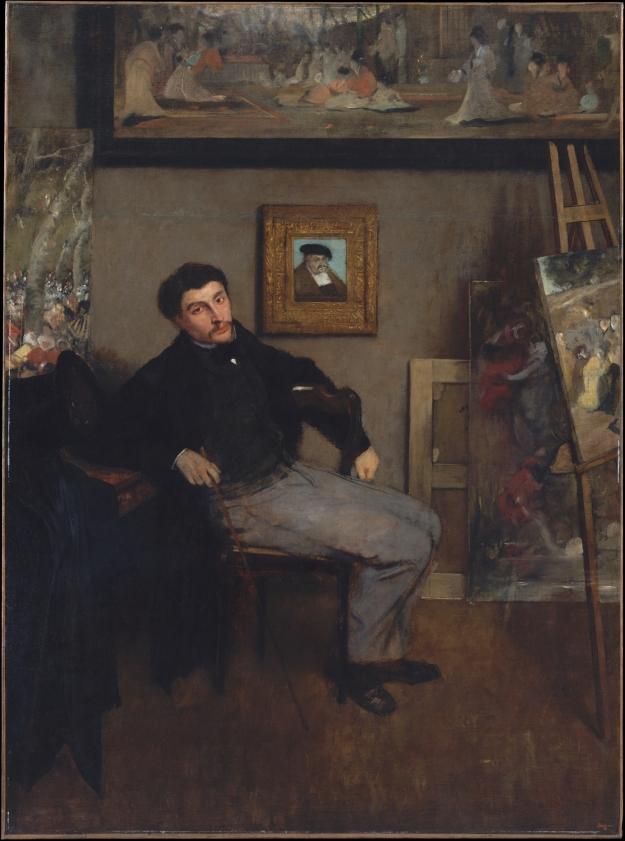

James Tissot excelled at accurate depictions and descriptive brushwork; he was not an innovator like his friends Edgar Degas, Edouard Manet and James Whistler. Though his style has been unfavorably compared to theirs over the decades, Degas once considered him far more skilled. In 1868, Tissot left copious technical notes for Degas on how to improve one of his paintings-in-progress, Interior (The Rape), at Degas’ apparent request; clearly, this was the relationship they had. Tissot knew what he was doing, and some found his artistic confidence irritating: one critic at this time observed that Tissot was dapper and personable, but thought him a little pretentious and a less-than-great artist “because he did what he wanted to do and as he wished to do it.”

James Tissot excelled at accurate depictions and descriptive brushwork; he was not an innovator like his friends Edgar Degas, Edouard Manet and James Whistler. Though his style has been unfavorably compared to theirs over the decades, Degas once considered him far more skilled. In 1868, Tissot left copious technical notes for Degas on how to improve one of his paintings-in-progress, Interior (The Rape), at Degas’ apparent request; clearly, this was the relationship they had. Tissot knew what he was doing, and some found his artistic confidence irritating: one critic at this time observed that Tissot was dapper and personable, but thought him a little pretentious and a less-than-great artist “because he did what he wanted to do and as he wished to do it.”

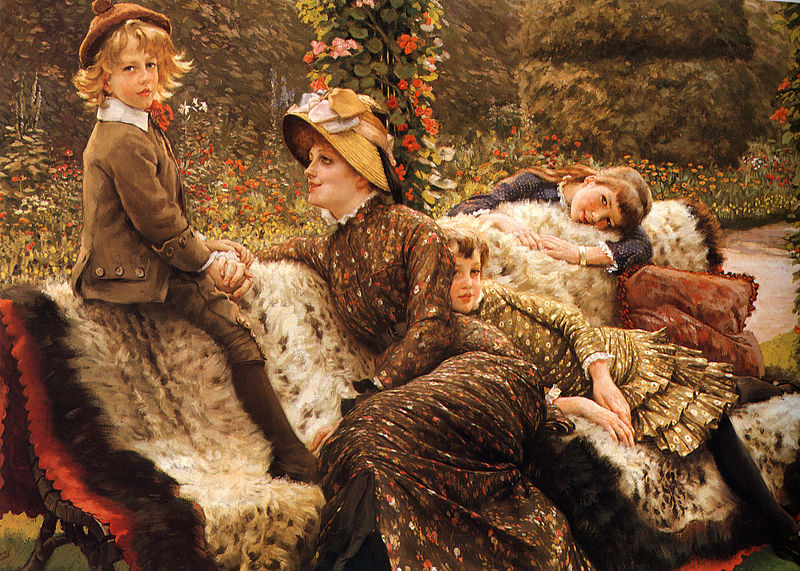

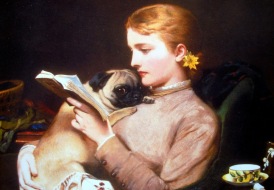

The 1874 catalogue records for Goupil’s art gallery in Paris include this painting as Le goûter (Afternoon tea). By 1883, Le goûter was in the collection of William H. Vanderbilt (1821 – 1885), who lived in a mansion at 660 Fifth Avenue, New York, that Vanderbilt’s wife, Alva, commissioned in 1878 from Richard Morris Hunt after William inherited the bulk of his father’s his $100 million estate in 1877. Built in a French Renaissance and Gothic style, the mansion was referred to as the Petit Château, and its grand interiors were furnished from trips to Europe, with items from antique shops and from “pillaging the ancient homes of impoverished nobility.”

The 1874 catalogue records for Goupil’s art gallery in Paris include this painting as Le goûter (Afternoon tea). By 1883, Le goûter was in the collection of William H. Vanderbilt (1821 – 1885), who lived in a mansion at 660 Fifth Avenue, New York, that Vanderbilt’s wife, Alva, commissioned in 1878 from Richard Morris Hunt after William inherited the bulk of his father’s his $100 million estate in 1877. Built in a French Renaissance and Gothic style, the mansion was referred to as the Petit Château, and its grand interiors were furnished from trips to Europe, with items from antique shops and from “pillaging the ancient homes of impoverished nobility.”

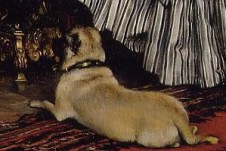

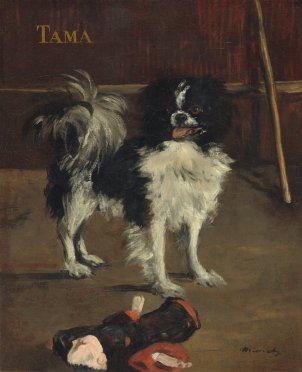

When the British invaded and looted the Chinese Imperial Palace in 1860 during the Second Opium War, they brought pug dogs back to England, where they were first exhibited in 1861.

When the British invaded and looted the Chinese Imperial Palace in 1860 during the Second Opium War, they brought pug dogs back to England, where they were first exhibited in 1861. b

b  c

c

e

e

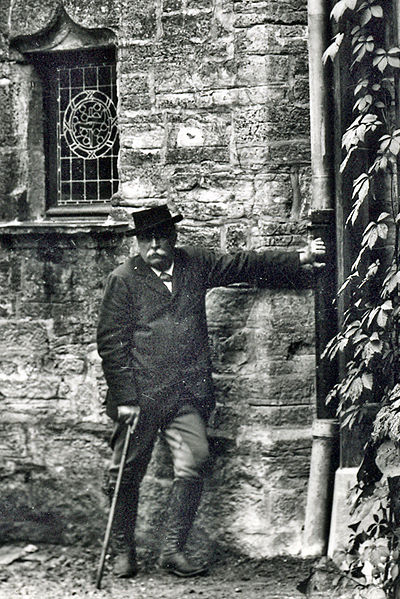

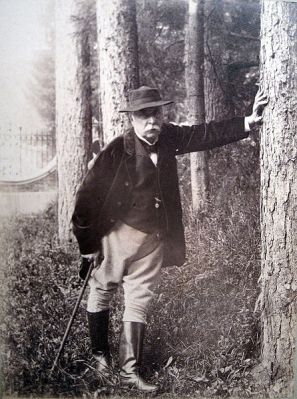

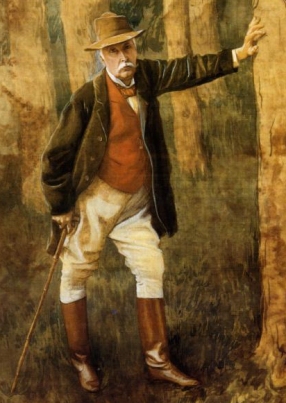

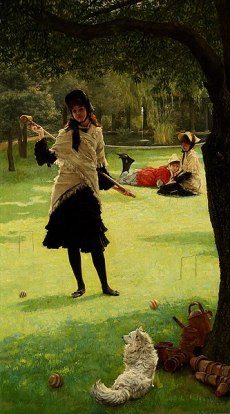

After emigrating to England with less than one hundred francs but with numerous British friends, Tissot received considerable help in establishing his career anew in London. Frances, Countess Waldegrave (1821-1879), who shared Tissot’s interest in spiritualism, hosted fabulous salons in London and at Strawberry Hill in Twickenham. Frequent guests included Gladstone, Disraeli, and the Prince and Princess of Wales. In 1871 – shortly after Tissot had fled the Bloody Week in Paris – the charming and “irresistible” Countess Waldegrave pulled strings to get Tissot a lucrative commission to paint a full-length portrait of her fourth husband, Chichester Fortescue (right). It was funded by a group of eighty-one Irishmen including forty-nine MPs, five Roman Catholic bishops and twenty-seven peers to commemorate his term as Chief Secretary for Ireland under Gladstone – as a present to his wife. Fortescue, later Baron Carlingford (1823 – 1898) was a politically ambitious Irishman and Liberal MP for County Louth from 1847 to 1868. In 1863, he married the politically influential Countess Waldegrave, previously the wife of the 7th Earl Waldegrave, who had chosen him out of the three or more men who wished to marry her. Fortescue had been in love with her for a decade before her elderly third husband died. Tissot may have included the perky white terrier-type dog at his feet as a way of humanizing a quiet, bookish man described as “pedantic” but capable of great love.

After emigrating to England with less than one hundred francs but with numerous British friends, Tissot received considerable help in establishing his career anew in London. Frances, Countess Waldegrave (1821-1879), who shared Tissot’s interest in spiritualism, hosted fabulous salons in London and at Strawberry Hill in Twickenham. Frequent guests included Gladstone, Disraeli, and the Prince and Princess of Wales. In 1871 – shortly after Tissot had fled the Bloody Week in Paris – the charming and “irresistible” Countess Waldegrave pulled strings to get Tissot a lucrative commission to paint a full-length portrait of her fourth husband, Chichester Fortescue (right). It was funded by a group of eighty-one Irishmen including forty-nine MPs, five Roman Catholic bishops and twenty-seven peers to commemorate his term as Chief Secretary for Ireland under Gladstone – as a present to his wife. Fortescue, later Baron Carlingford (1823 – 1898) was a politically ambitious Irishman and Liberal MP for County Louth from 1847 to 1868. In 1863, he married the politically influential Countess Waldegrave, previously the wife of the 7th Earl Waldegrave, who had chosen him out of the three or more men who wished to marry her. Fortescue had been in love with her for a decade before her elderly third husband died. Tissot may have included the perky white terrier-type dog at his feet as a way of humanizing a quiet, bookish man described as “pedantic” but capable of great love.

g

g

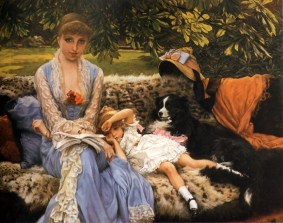

The Victorians set great store by animals, and dogs especially exemplified loyalty and the affection and comfort of domestic life. In J.E Millais’ The Black Brunswicker (1860), left, the dog sweetly joins the woman in begging the soldier not to depart for battle.

The Victorians set great store by animals, and dogs especially exemplified loyalty and the affection and comfort of domestic life. In J.E Millais’ The Black Brunswicker (1860), left, the dog sweetly joins the woman in begging the soldier not to depart for battle. i

i

But James Tissot’s depictions of dogs had more in common with those of his friends in Paris than with those in sentimental Victorian paintings.

But James Tissot’s depictions of dogs had more in common with those of his friends in Paris than with those in sentimental Victorian paintings. k

k

While dogs had symbolic meaning in art, James Tissot, a shrewd businessman, likely included dogs in many of his compositions because they appealed to Victorian sensibilities and because they were part of the life around him that he recorded so faithfully.

While dogs had symbolic meaning in art, James Tissot, a shrewd businessman, likely included dogs in many of his compositions because they appealed to Victorian sensibilities and because they were part of the life around him that he recorded so faithfully. If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download