Even as James Tissot’s paintings were collected and valued during his early career in Paris and once he moved to London after the fall of the Paris Commune, he himself was a collector. By the early to mid-1870s, as he began rebuilding his career in Victorian England, Tissot owned paintings by his struggling friends Camille Pissarro (1830 – 1903), Édouard Manet (1832 – 1883) and Edgar Degas (1834 – 1917), and he helped Berthe Morisot (1841 –

1895) further her painting career.

By early 1871, Tissot had purchased a painting by Pissarro. It has not been identified, but it was a canvas that Pissarro, who had fled to London in December 1870 during the Franco-Prussian War, submitted unsuccessfully to the Royal Academy in the spring.

![]()

The Grand Canal, Venice (Blue Venice), by Édouard Manet. Oil on canvas, 23 1/8 x 28 1/8 in. (58.7 x 71.4 cm.) Shelburne Museum, Shelburne, Vermont, U.S.A. Photo: wikipaintings.org

Tissot also owned Manet’s The Grand Canal, Venice (Blue Venice), 1875, (oil on canvas, 23 1/8 x 28 1/8 in. (58.7 x 71.4 cm.), The Shelburne Museum, Shelburne, Vermont). Tissot and Manet travelled to Venice together in the fall of 1874, and Tissot bought Manet’s Blue Venice on March 24, 1875 for 2,500 francs. Manet badly needed the income. Tissot hung the painting in his home in St. John’s Wood, London, and did his best to interest English dealers in Manet’s work. Manet died on April 30, 1883; in 1884, while Tissot owned it, Blue Venice was included in a retrospective exhibition of Manet’s work, organized as a tribute, in Paris. By August 25, 1891, Tissot sold the picture to contemporary art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel (1831 – 1922), and in 1895, Durand-Ruel sold it as Vue de Venise (View of Venice) to Mr. and Mrs. Henry O. Havemeyer, New York, for $12,000. A prominent art collector, Mrs. Havemeyer (1855 – 1929) named the painting Blue Venice. After the deaths of the Havemeyers, their youngest child, Electra Havemeyer Webb (1888-1960), owned Blue Venice from 1929 until her death. She had founded The Shelburne Museum in Vermont in 1947, and Manet’s painting entered the collection there in 1960.

Tissot helped Berthe Morisot as well, but with advice. In 1875, Berthe wrote to her sister, Edma, during her honeymoon in England with Manet’s brother, Eugène, “we left [Cowes]… We went to see Tissot, who does very pretty things that he sells at high prices; he is living like a king. We dined there. He is very nice, a very good fellow, though a little vulgar. We are on the best of terms; I paid him many compliments, and he really deserves them.” Berthe also wrote, “Today I shall hasten to that handsome Stanley, the bishop of Westminster Abbey, to whom I have a letter of introduction from the Duchess…Tissot tells me he is a very important personage, who can open all doors for us,” and she added, “Tissot tells me that during the regatta week at Cowes we saw the most fashionable society in England.”

During the same trip, Berthe wrote to her mother, “[I was dragged out of bed] just now by a letter from Tissot – an invitation to dinner for tomorrow night. I had to get up and ransack everything to find a clean sheet of paper in order to reply…I don’t mind seeing someone; it will be a change from the boarding-house routine.” Later, she followed this with, ”We went to see him yesterday. He is very well installed, and is turning out excellent pictures. He sells for as much as 300,000 francs at a time. What do you think of his success in London? He was very amiable, and complimented me although he has probably never seen any of my work.”

![Horses in a Meadow (1871), by Edgar Degas.]()

Horses in a Meadow (1871), by Edgar Degas. Oil on canvas, 12 1/2 x 15 3/4 in. (31.8 x 40 cm.) Chester Dale Fund, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Photo by Lucy Paquette.

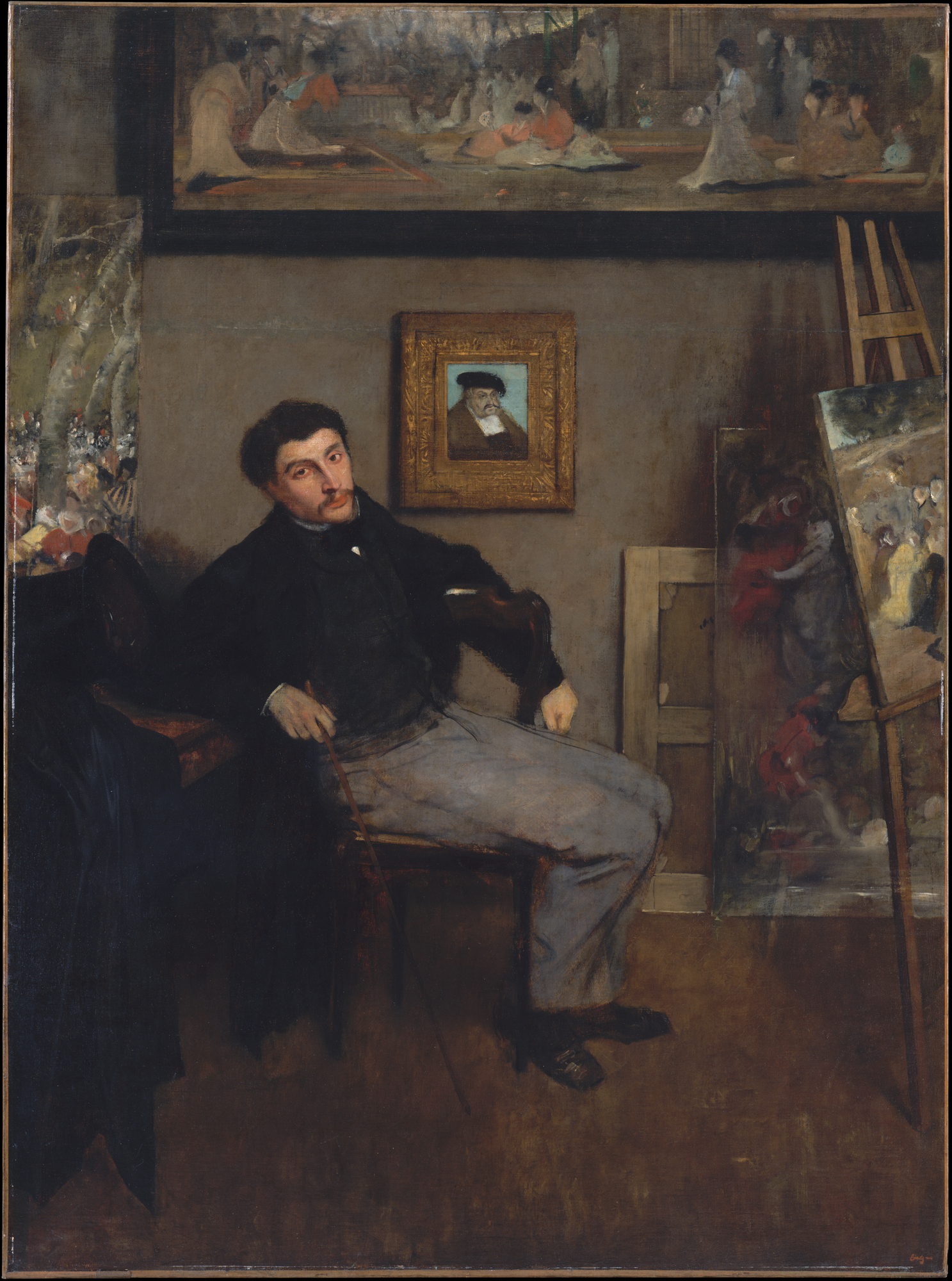

Tissot had met Degas in 1859, when they both studied art under Louis Lamothe (1822 – 1869), and the two had become close friends. In 1867-68, Degas painted a portrait of James Tissot, then 31-32 years old. Within a few years, Tissot owned two oil paintings by Degas: Horses in a Meadow (1871, oil on canvas, 12 1/2 x 15 3/4 in. (31.8 x 40 cm.), National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.) and Woman with Binoculars (1875-76, oil on cardboard, 18 7/8 x 11 7/8 in. (48 x 32 cm.), Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Galerie Neue Meister [State Art Collections, Dresden, New Masters Gallery]).

Horses in a Meadow was purchased from Degas in 1872 by Durand-Ruel, who sold it in January, 1874 for under 1,000 francs to opera baritone Jean Baptiste Faure (1830-1914), Paris. Faure returned it to Degas, who gave it as a gift to James Tissot. In 1890, Tissot sold Horses in a Meadow to Durand-Ruel for an unknown amount. The picture was in the possession of Durand-Ruel until his death in 1922, then with his estate through 1925. Mr. and Mrs. Jean D’Alayer owned it from 1951 to 1960; Mrs. D’Alayer was Paul Durand-Ruel’s granddaughter. By 1991, New York art dealer Janet Traeger Salz had Horses in a Meadow, and the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. purchased it in 1995 with the Chester Dale Fund.

![Woman with Binoculars (1875-76), by Edgar Degas. oil on cardboard, 18 7/8 x 11 7/8 in. (48 x 32 cm.) Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Galerie Neue Meister (State Art Collections, Dresden, New Masters Gallery).]()

Woman with Binoculars (1875-76), by Edgar Degas. oil on cardboard, 18 7/8 x 11 7/8 in. (48 x 32 cm.) Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Galerie Neue Meister (State Art Collections, Dresden, New Masters Gallery).

Degas gave his painting of a woman named Lyda, titled Woman with Binoculars, to Tissot as a gift right after finishing it in 1876. It remained in Tissot’s possession until January 11, 1897, when he sold it to Durand-Ruel for 1,500 francs. Durand-Ruel sold it to H. Paulus in November of that year for 6,000 francs. By 1907, Dresden art historian and collector Woldemar von Seidlitz owned Woman with Binoculars; it is possible that he bought it directly from Durand-Ruel, because he often was in Paris. When he died in January, 1922, he bequeathed the painting to his nephew, also named Woldemar von Seidlitz, from whom it was purchased in the same year for the Galerie Neue Meister.

American scholar and collector Michael Wentworth (1938-2002) wrote, “[Tissot’s] friendship with Degas came to an…unhappy end when Tissot sold two pictures Degas had once given him for reasons that, however inexplicable, can hardly have been financial and today still appear quite gratuitously insulting.”

Christopher Wood (1941 – 2009), a former director at Christie’s, London and later an art dealer at the forefront of the revival in interest of Victorian art in the late 20th century with his gallery in Belgravia, wrote that Tissot’s “long, difficult and stormy relationship with Degas finally ended in 1895 [sic] when Tissot sold a painting which Degas had given him.”

Tissot scholar Willard E. Misfeldt (a professor of Art History at Bowling Green State University, Ohio from 1967 to 2001), suggested that a reason for the rupture between Tissot and Degas “might have been Degas’ penchant for expressing himself bluntly and openly, regardless of the fact that his statements were often uncomplimentary.” But Misfeldt then stated, “Tissot had always been a clever entrepreneur, able to make a considerable fortune from his art where Degas had failed, and when Tissot later sought to turn a profit by selling something he had gotten from Degas the latter was understandably incensed.” He notes that this incident took place in 1897.

Scholars consistently portray this break in a nearly forty-year friendship as Tissot’s fault, for supposedly being mercenary, with Degas being wronged. Théodore Duret (1838 –1927; a wealthy cognac dealer and art critic who was an early supporter of the Impressionists), painter Henri Michel-Lévy (1845–1914; a wealthy publisher’s son), Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841–1919) and James Tissot all sold works that they had bought from Degas or received as gifts. “It is sad,” Degas said, “to live surrounded by scoundrels.” Yet Degas himself capitalized on the increasing value of his work.

In 1893, Degas’ Absinthe was purchased for 21,000 francs. Degas offended American painter Mary Cassatt (1844 – 1926) two years later when he asked the Havemeyers three thousand dollars for a picture Cassatt had sold to them, for him, for one thousand dollars in 1893; the Havemeyers paid the increased price, but Degas lost Cassatt’s friendship for a long time.

In 1896, Degas’ work received the official stamp of approval when seven of his pastels were accepted by the Musée de Luxembourg. Considering the small sum (1,500 francs) for which Tissot sold Woman with Binoculars in 1897, greed would have been an unlikely motivation. After all, Tissot had earned a total of 1,200,000 francs during his eleven years painting in London, and he was now creating a sensation with his Bible illustrations, on which he had labored from 1886 to 1894. He had made a third trip to Palestine in 1896 to gather further impressions, and his illustrations were exhibited in London in 1896 and in Paris, for the second time since 1894, in 1897. One observer noted that, “women were seen to sink down on their knees as though impelled by a superior force, and literally crawl round the rooms in this position, as though in adoration.” Tissot arranged to have the Bible pictures published in 1896-97, before the 1898 American tour, and he received a million francs for the reproduction rights. He soon made arrangements with other publishers, in England and America.

It is possible that Tissot sold Manet’s Blue Venice in 1891 for a profit, after Manet’s 1883 death had made his work valuable. Perhaps Tissot sold Degas’ Horses in a Meadow in 1890 after one of Degas’ early dance pictures was sold at auction for 8,000 francs that year. But why did he sell Woman with Binoculars in 1897, especially for a mere 1,500 francs when it was worth four times that?

![]()

Alfred Dreyfus stripped of rank, by Henri Meyer (1844–1899). Le Petit Journal, January 13, 1895. (Photo: Wikimedia.org)

One possible explanation for Tissot’s sale of Woman with Binoculars can be found in the fact that from 1894, an evolving political scandal polarized France. A young French artillery officer of Jewish descent, Captain Alfred Dreyfus, was convicted of treason and sentenced to life imprisonment for allegedly having offered confidential French military documents to the German Embassy in Paris. In 1896, new evidence showed that the act was committed by a French Army major; the evidence was suppressed, and on January 10, 1898, a military court acquitted the major. The Army, using forged documents, then accused Dreyfus of additional charges.

The French were divided into two camps: The Dreyfusards, who were sure an innocent man had been sent to prison, and the anti-Dreyfusards, who were adamant that the general staff of France’s Army should not be undermined.

Dreyfusards, considered the intellectuals, included painters Claude Monet and Pissarro, writer Émile Zola; and author and playwright Ludovic Halévy and his family.

The anti-Dreyfusards, considered the nationalists and adherents of the Catholic revival, included Degas, Cézanne, Renoir, poet and essayist Paul Valéry, Degas’ old friend Henri Rouart and his four sons.

A turning point came on January 13, 1898, when Zola’s open letter to the President of France was published on the front page of a Paris newspaper. Zola accused the French Army of obstruction of justice and anti-Semitism in its wrongful conviction of Alfred Dreyfus to life imprisonment.

![]()

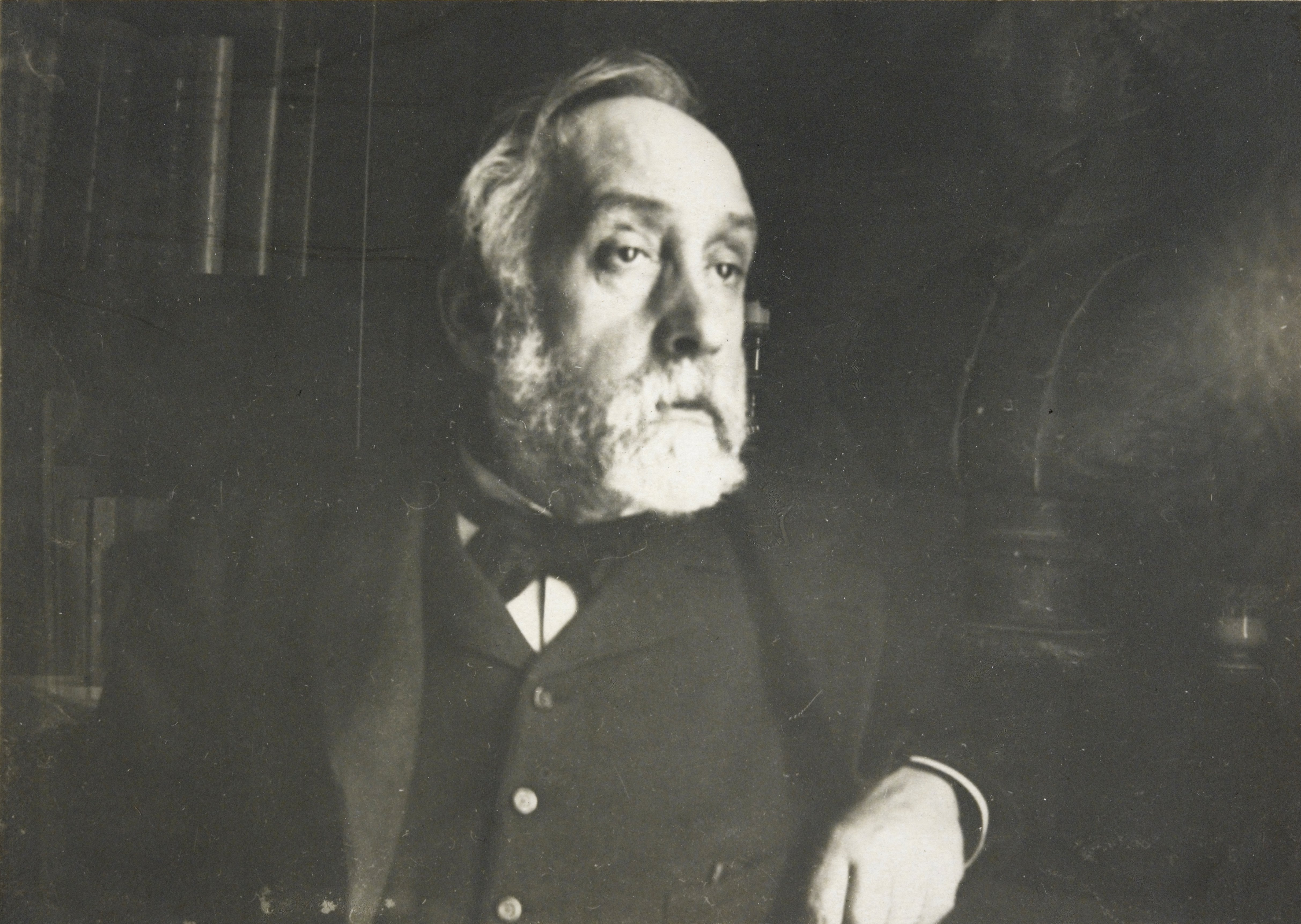

Photographic self-portrait (probably autumn 1895), by Edgar Degas. Gelatin silver print, 4 11/16 x 6 9/16 in. Harvard Art Museum/Fogg Museum. Photo: Wikimedia.org

Degas ended his fifty-year friendship with his old schoolmate, playwright and novelist Ludovic Halévy (1834 – 1908), over differences regarding the Dreyfus Affair, in the first weeks of January, 1898. Degas also broke with several others, including Pissarro, at this time.

Paul Valéry (1871 – 1945) wrote, “Degas had political ideas. They were simple, peremptory, essentially Parisian. At the slightest indication he inferred, he exploded, he broke off. ‘Adieu, Monsieur,’ and he turned his back on the adversary forever…Politics in the Degas style were inevitably like himself – noble, violent, impossible.”

![Français : James Tissot Français : James Tissot]()

James Tissot

By November, 1895, Degas was openly anti-Semitic. James Tissot had numerous Jewish friends, including Sir Julius Benedict (1804 – 1885), a German-born composer and conductor whom Tissot portrayed as the pianist in his 1875 painting, Hush! (The Concert); Algernon Moses Marsden (1847 – 1920), whose portrait he painted in 1877 and who, for a time, acted as his art dealer; Camille Pissarro; and, by one account, English Pre-Raphaelite painter Simeon Solomon (1840 –1905).

Perhaps Degas initiated the rift with Tissot, who then sold Woman with Binoculars, a gift Degas had given him when they were dear friends.

Interestingly, Degas kept his 1867-68 portrait of Tissot until his death in 1917. It is now on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in Gallery 810.

![]()

Portrait of James Jacques Joseph Tissot (1836–1902), c. 1867-68, by Edgar Degas. Oil on canvas, 59 5/8 x 44 in. (151.4 x 111.8 cm.) Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1939. (Photo: Wikimedia.org)

Related posts:

Tissot and Manet attempt to help their friend Degas, 1868

Who was Algernon Moses Marsden?

I am grateful to the following individuals for sharing information on the provenance of two of the paintings discussed in this article:

Dr. Gilbert Lupfer and Juliane Au, Intern

Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

and

Leslie Wright, Public Relations and Marketing Manager

Shelburne Museum, Shelburne, Vermont

© 2013 by Lucy Paquette. All rights reserved.

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download free Kindle reading apps for PCs, Smartphones, tablets, and the Kindle Cloud Reader to read The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot. Read reviews.

![CH377762]() The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot, brings Tissot’s world from 1870 to 1879 alive in a story of war, art, Society glamour, love, scandal, and tragedy.

The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot, brings Tissot’s world from 1870 to 1879 alive in a story of war, art, Society glamour, love, scandal, and tragedy.

Illustrated with 17 stunning, high-resolution fine art images in full color

Courtesy of The Bridgeman Art Library

(295 pages; ISBN (ePub): 978-0-615-68267-9). See http://www.amazon.com/dp/B009P5RYVE.

![]()

![]()

The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot, brings Tissot’s world from 1870 to 1879 alive in a story of war, art, Society glamour, love, scandal, and tragedy.

The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot, brings Tissot’s world from 1870 to 1879 alive in a story of war, art, Society glamour, love, scandal, and tragedy.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)