As of January, 2015, there are twenty-six oil paintings by James Tissot in public art collections in the continental U.S. and Puerto Rico, and seventeen of them are registered with the Nazi Era Provenance Internet Portal (NEPIP).

The Nazi Era Provenance Internet Portal (NEPIP) at http://www.nepip.org/ provides a searchable online registry of objects in U.S. museum collections that changed hands in Continental Europe during the Nazi era (1933-1945). NEPIP is a single point of contact to 175 U.S. museums whose staff have come to recognize, since the late 1990s, that objects looted, seized, and illegally sold during the Nazi era may have made their way into U.S. museum collections in the decades since the war. NEPIP was established in 2006 by the American Alliance of Museums in Arlington, Virginia; its website is http://www.aam-us.org/.

NEPIP contains information only about objects that:

- were created before 1946 and acquired after 1932,

- underwent a change of ownership between 1932 and 1946, and

- were or might reasonably be thought to have been in Continental Europe between those dates.

An object’s inclusion on NEPIP does not indicate that the works are suspect, but that its provenance during the Nazi era is unclear or not yet fully documented.

The seventeen Tissot oils registered with the NEPIP from public collections worldwide are listed below with images and the information on the provenance, or history of ownership, that is known.

Promenade on the Ramparts (1864)

Tissot’s Promenade on the Ramparts (1864) [oil on board; 52 by 44.4 cm] was gifted to Stanford University in California in 1968, by petroleum geologist Robert Sumpf (1917 – 1994), who had earned his B.S. in geology there in 1941.

Gentleman in a Railway Carriage

Gentleman in a Railway Carriage (1872)

Tissot’s 1872 image of the modern commuter, Gentleman in a Railway Carriage [24 15/16 by 16 15/16 in./63.30 by 43.00 cm], was purchased for The Worcester Art Museum, Massachusetts by the Alexander and Caroline Murdock de Witt Fund in 1965.

London Visitors

London Visitors (c. 1874)

Tissot exhibited London Visitors (c. 1874) [63 by 44.9 in./160 by 114 cm] at the Royal Academy in 1874.

The painting once had been in the collections of Mrs. Bannister; M. Bernard, London; and Robert Frank, London, and it was exhibited in 1937 at the Leicester Galleries in London.

In 1951, London Visitors was acquired by the Toledo Museum of Art in Ohio.

Hide and Seek

Hide and Seek (1877)

Hide and Seek (1877) was sold at Christie’s, London in 1957 for $ 2,379 USD/£ 850 GBP, then at Sotheby’s, London in 1963 for $ 6,159 USD/£ 2,200 GBP. Mrs. C. Behr, London, owned it until at least 1967, after which it belonged to Julian Spiro, Esq. In 1976, Christie’s, London sold the painting for $ 33,002 USD/£ 20,000 GBP. Two years later, Hide and Seek was purchased from the Herman Shickman Gallery in New York with the Chester Dale Fund by the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

July (Speciman of a Portrait

July (Speciman of a Portrait, 1878)

Tissot exhibited July (Speciman of a Portrait) along with nine other paintings at London’s Grosvenor Gallery in 1878, the year it was painted.

At some point, another artist painted a frizzy red hairstyle (probably considered more up-to-date) on Kathleen Newton.

The painting was acquired by the Cleveland Museum of Art, Ohio by the bequest of Noah L. Butkin in 1980.

The Dance of Death (1860)

The Dance of Death was exhibited at the Salon in 1861 under the title, Voie des fleurs, voie des pleurs (Path of Flowers, Way of Tears). Tissot offered this to a collector at what he considered (or shrewdly pretended to consider) a low price of 5,000 francs. In a private collection in Philadelphia until it was purchased from Julius H. Weitzner (1896 – 1986), a leading dealer in Old Master paintings in New York and London, by the Rhode Island School of Design Museum in Providence in 1954, it measures 14 5/8 by 48 3/16 by 1 1/2 in., or 37.1 by 122.4 by 3.8 cm.

The Women of the Chariots

Women of Paris: The Women of the Chariots (also called The Circus, 1883-1885)

The Women of the Chariots, also called The Circus, was exhibited in Paris in 1885 and in London in 1886 as Ladies of the Cars.

It is the second in the “La Femme à Paris” (“Women of Paris”) series, painted sometime before mid-1884.

The Women of the Chariots [57 ½ by 39 5/8”/146 by 100.65 cm], was sold by Julius Weitzner to Walter Lowry, who gifted it to the Rhode Island School of Design Museum in Providence, in 1958.

The Two Friends (c. 1881) and Interior of the Louvre (c. 1883-85).

In the collection of the Rhode Island School of Design Museum in Providence, but not on public display, are Tissot’s The Two Friends and In the Louvre.

Women of Paris: The Circus Lover (1885)

Women of Paris: The Circus Lover

Women of Paris: The Circus Lover is another painting in Tissot’s “La Femme à Paris” series.

The year it was painted, 1885, it was exhibited from April 19 – June 15 as part of the series of fifteen canvases at Galerie Sedelmeyer, Paris, and in 1886, it was included with the series exhibited at Arthur Tooth and Son, London.

By 1889, The Circus Lover was in the possession of E. Simon, who sold it on March 30, 1889 at Christie’s, London, to Mr. King. It later was with the Goupil Gallery, London; there is a label on the reverse of the stretcher from William Marchant and Co., The Goupil Gallery, London. The painting next belonged to The Hon. Mrs. Arthur Henniker (Inger Margueretta Hutchinson) (d. 1923), Suffolk, England. By 1955, it was in the possession of Gerald M. Fitzgerald, London, who lent the painting to the Graves Art Gallery, Sheffield, that May for “James Tissot (1836-1902): An Exhibition of Paintings, Drawings, and Etchings.” Mr. Fitzgerald sold The Circus Lover on July 26, 1957 at Christie’s, London, to Mr. Lloyd, director of Marlborough Fine Art, Ltd., London, for $ 3,219 USD/£ 1,150 GBP, and on February 13, 1958, Marlborough Fine Art sold the to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Massachusetts for $ 5,000 as Amateur Circus.

The Emigrants (1873)

From information I have pieced together from various Tissot scholars, there were two versions of The Emigrants (1873), and Tissot exhibited either the original or the replica at the Grosvenor Gallery in 1879.

From information I have pieced together from various Tissot scholars, there were two versions of The Emigrants (1873), and Tissot exhibited either the original or the replica at the Grosvenor Gallery in 1879.

The original was a large oil on canvas, measuring 28 by 40 in./71.12 by 101.6 cm. This painting was once in the collection of the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, but was somehow damaged and cut down in height. It is considered lost.

It is now known only through the replica that Tissot produced. This smaller painting, an oil on panel also called The Emigrants (1873), measures 15.75 by 7.5 in./40.2 by 19 cm). As of at least 1984, it was in a private collection in New York. However, in 1991, it was gifted to the Speed Museum by Mr. and Mrs. W. Armin Willig. [Winston] Armin Willig (1912 – 1992) was an alumnus of the University of Louisville, and he became a prominent businessman in the area. He was appointed by the Governor of Kentucky to the post of Jefferson County judge after the incumbent County judge was killed in an automobile accident, serving from September 29, 1969 until January 4, 1970.

At the Falcon Inn, Waiting for the Ferry (1874)

At the Falcon Inn (Waiting for the Ferry

According to my research, Tissot’s Waiting for the Ferry at the Falcon Tavern (1874) was exhibited at Nottingham Castle, and at Newcastle-on-Tyne in 1887. It then was in the collection of James Hall, Esq., a prominent collector of Pre-Raphaelite art, in Newcastle-upon-Tyne. It was passed on to his son, Dr. Wilfred Hall, of Newcastle. His daughter, Mrs. Edward Reeves of Winchester in Hampshire, sold the painting at Christie’s, London in 1954 to the John Nicholson Gallery, New York for $ 4,339 (£ 1550).

In 1955, Mrs. Blakemore Wheeler [1887 – 1964, née Minnie Norton Marvin] of Louisville, Kentucky, who had been on the board of the Speed Museum since 1939, began collecting art. The daughter of a wealthy Louisville physician on the faculty of the University of Louisville Medical School and the wife of a prominent Realtor, she had no children. By 1957, she owned this version of Tissot’s Waiting for the Ferry at the Falcon Tavern, and in 1963, she gifted it to the Speed.

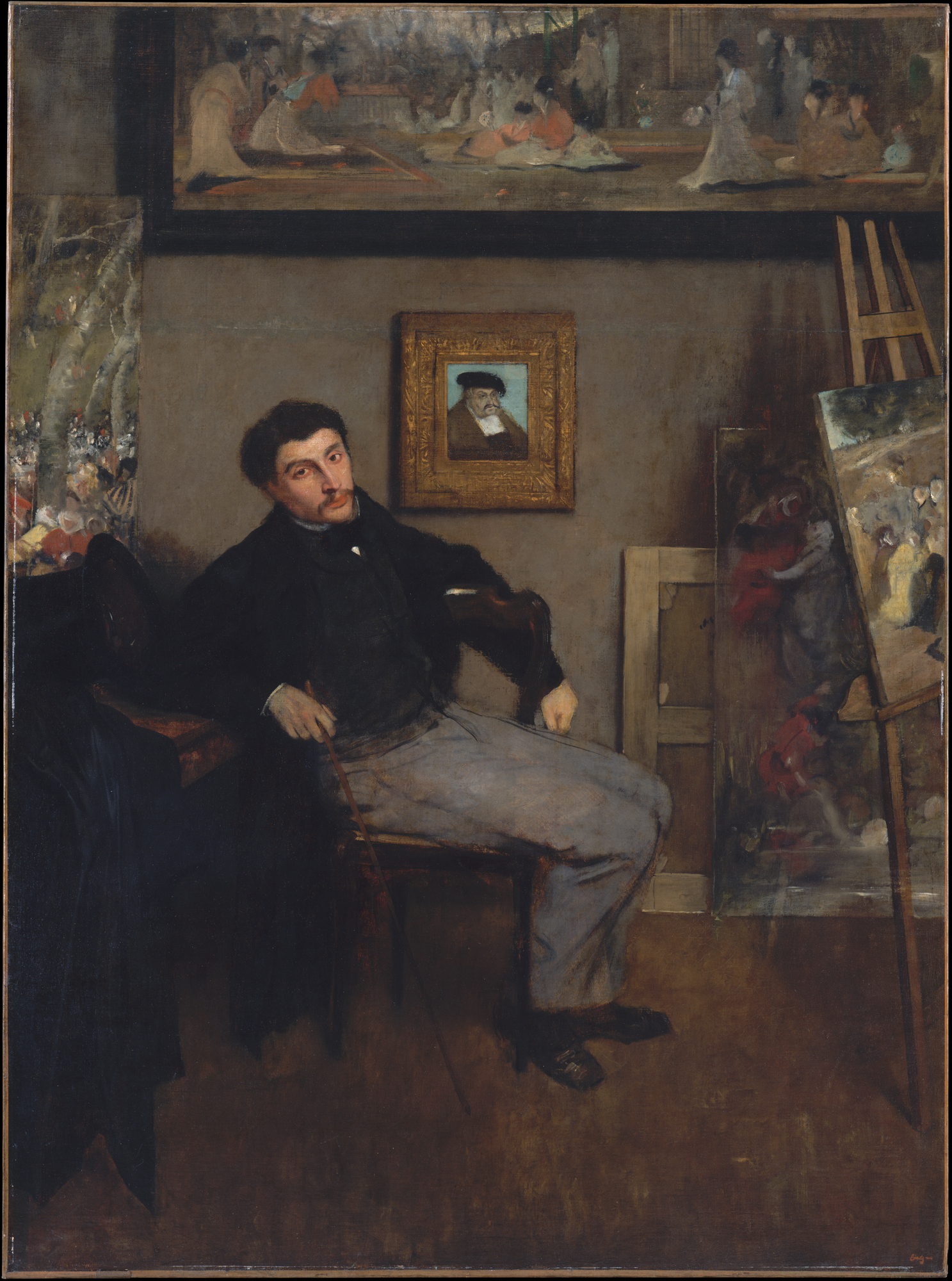

Portrait of Eugène Coppens de Fontenay (1867)

Portrait of Eugène Coppens de Fontenay (1867), by James Tissot. 27 by 15 in. (68.58 by 38.10 cm). Philadelphia Museum of Art. Photo by Lucy Paquette.

In 1867, James Tissot painted Portrait of Eugène Coppens de Fontenay (1824 –1896), the president of the exclusive Jockey Club in Paris. Married in 1853, Eugène Aimé Nicolas Coppens de Fontenay had three children.

His daughter, Marthe Jeanne-Marie (1854 – 1898) , married Henri, Comte de Meffray [Henri Meffray de Césargues (1846-1927)] in 1876; the couple had two children and at least three grandchildren. Eugène’s second daughter, Françoise, was born in 1855, but there is no further information on her.

His son, Robert Coppens de Fontenay (1858 – 1925), became a diplomat with the Belgian legation. He married in 1899 and had a son, Jacques Coppens de Fontenay (c. 1900- 1991), who sold the portrait at Christie’s, London, on March 5, 1971 to Holstein for $ 4,352 USD/£ 1,800 GBP. The picture was with the Herman Shickman Gallery, New York, by October 1971 and was purchased by the City of Philadelphia with the W. P. Wilstach Fund on March 14, 1972.

Young Women Looking at Japanese Articles (1869)

Young Women Looking at Japanese Articles (1869)

In 1869, Tissot assimilated his expanding collection of Japanese art and objets into elegant compositions in three similar paintings featuring young women looking at Japanese objects.

By the 1930s, the version below was hanging in an interior decorator’s store on Third Street in Cincinnati, Ohio, and was purchased by Dr. Henry M. Goodyear; he and his wife gifted Tissot’s picture to the Cincinnati Art Museum in 1984.

Tea

Tea (1872)

Tea (1872) [oil on wood, 26 by 18 7/8 in./66 by 47.9 cm] was in a private collection in Rome, Italy in 1968.

It was with Somerville & Simpson, Ltd., London, by 1979-81, when it was consigned to Mathiessen Fine Art Ltd., London.

It was purchased from Mathiessen by Mr. and Mrs. Charles Wrightsman, New York. Upon Mr. Wrightsman’s death in 1986, Mrs. Wrightsman owned it until 1998, when she gifted it to the Met.

Spring Morning (c. 1875) [oil on canvas, 22 by 16 3/4 in./55.9 by 42.5 cm] was in the possession of Thomas McLean, London, until about 1901; at some point after that, it was with Goupil, London.

It was sold by Sotheby’s Belgravia, London, on March 23, 1981, as Matinée de printemps, for £40,000 to Mr. and Mrs. Charles Wrightsman, New York. Mrs. Wrightsman gifted it to the Met in 2009.

In Full Sunlight (En plein soleil, c. 1881)

In Full Sunshine

In Full Sunlight (En plein soleil, c. 1881) [oil on wood, 9 3/4 by 13 7/8 in./24.8 by 35.2 cm] was with Lenz Fine Arts, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, until 1976, when it was sold to Williams and Son, London. That firm sold to the painting to Stair Sainty Gallery, London, where it was purchased in 1976 by Victor Hervey, 6th Marquess of Bristol (1915 – 1985), London. In 1983, the Marquess sold it back to Stair Sainty, where it was purchased that year by Mr. and Mrs. Charles Wrightsman, New York.

Mrs. Charles Wrightsman kept the picture until 2006, when she gifted it to the Met.

If you have questions about any of these Tissot paintings, please contact the participating museum.

Related posts:

Tissot in the U.S.: The Midwest

Tissot in the U.S.: The Speed Museum, Kentucky

Tissot in the U.S.: The Mid-Atlantic

Tissot in the U.S.: New England

© 2016 by Lucy Paquette. All rights reserved.

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download free Kindle reading apps for PCs, Smartphones, tablets, and the Kindle Cloud Reader to read The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot. Read reviews.

The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot, brings Tissot’s world from 1870 to 1879 alive in a story of war, art, Society glamour, love, scandal, and tragedy.

The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot, brings Tissot’s world from 1870 to 1879 alive in a story of war, art, Society glamour, love, scandal, and tragedy.

Illustrated with 17 stunning, high-resolution fine art images in full color

Courtesy of The Bridgeman Art Library

(295 pages; ISBN (ePub): 978-0-615-68267-9). See http://www.amazon.com/dp/B009P5RYVE.

.jpg)

The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot, brings Tissot’s world from 1870 to 1879 alive in a story of war, art, Society glamour, love, scandal, and tragedy.

The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot, brings Tissot’s world from 1870 to 1879 alive in a story of war, art, Society glamour, love, scandal, and tragedy.

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download

Kathleen Newton is immediately recognizable in the caped greatcoat that Tissot portrayed her wearing, in numerous paintings including two versions of Waiting for the Ferry (c. 1878), The Ferry (c. 1879, Private Collection), Foreign Visitors to the Louvre (c. 1880), Departure Platform, Victoria Station (c. 1880), “Goodbye” – On the Mersey (c. 1881), The Terrace of the Trafalgar Tavern, Greenwich, London (c. 1878) [left], and By Water (c. 1881-82), and even after her death in The Cab Road, Victoria Station (also known as Departure Platform, Victoria Station, 1895).

Kathleen Newton is immediately recognizable in the caped greatcoat that Tissot portrayed her wearing, in numerous paintings including two versions of Waiting for the Ferry (c. 1878), The Ferry (c. 1879, Private Collection), Foreign Visitors to the Louvre (c. 1880), Departure Platform, Victoria Station (c. 1880), “Goodbye” – On the Mersey (c. 1881), The Terrace of the Trafalgar Tavern, Greenwich, London (c. 1878) [left], and By Water (c. 1881-82), and even after her death in The Cab Road, Victoria Station (also known as Departure Platform, Victoria Station, 1895).

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download

© 2017 by Lucy Paquette. All rights reserved.

© 2017 by Lucy Paquette. All rights reserved. b

b  c

c

b

b  c

c

b

b

b

b  c

c

b

b

b

b  c

c

b

b

b

b  c

c

b

b  c

c

b

b  c

c  d

d

b

b  c

c

b

b  c

c

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download